Voting Systems – Electing Leaders

Getting the general public’s input on how a country should be run is a fundamental tenet of democracy. This has to be done in a way that is both systematic and able to be considered fair, which is difficult to achieve without incorporating voting in some way, shape or form.

Perhaps in very small groups, consensus building can be used to bypass the need for voting, but as groups of people get larger, the number of possible disagreements to resolve and compromises required to reach consensus grow rapidly. This is one of the reasons why teams within a company are generally recommended to be smaller than 20 people, with 5-7 often being considered ideal.

Given that no country is this small, the need to implement a system of voting is something of an inevitability. Unfortunately, there are many ways in which voting systems can introduce issues that stand in the way of the democratic process. Issues such as gerrymandering, hyper-partisanship and voter apathy are often a direct result of the system that is used.

Without consensus building being strictly required, voting introduces the risk of Tyrrany of the Majority. Judicial systems are therefore a critical component of modern democracies, which serve to protect minority voices, but it is an imperfect system – there is no rule of law that cannot be replaced by a large enough majority. In the end though, even a consensus based system in a tiny community isn’t immune to this – a large enough majority that is sufficiently well coordinated could just decline to find a consensus, and kick out the minority (or worse).

With this caveat established as unavoidable however, there are still a great many other issues evident in the voting systems of most modern democracies that should be able to be improved upon.

Different Purposes

Quite apart from voting methods themselves, there are four very different purposes for which voting can be used:

- Leaders (Presidential/Gubernatorial Systems)

- People voting for the leader of a nation, state, department or entity

- These are “single seat” positions – there may be multiple people running for the office, but only one can win any particular office

- Referenda (Direct Democracy)

- People voting directly on specific issues or laws

- Can be yes/no questions, or a choice of more options depending on the approach

- Representatives (Representative Democracy/Parliamentary Systems)

- People voting for representatives to pursue their interests in the corridors of power

- The combination of politicians that are appointed are supposed to be in some way representative of the population

- Procedures (Intra-governmental decision making)

- Politicians within a representative democracy use voting to decide on issues and to pass laws

Although on the face of it, these four purposes could be considered very similar (and indeed are treated similarly in most democracies), they each encounter very different issues. If we are to try to improve on existing approaches, it will be worth separating them out, and considering each of them on its own.

In this post, I shall focus on the first of these, with the other three following in posts of their own.

Electing Leaders

Electing someone to a single, stand-alone office such as a president or a governor is usually is a fairly common goal and as such, much ink has been spilled over the best way to do this.

Unlike with representatives, the stand-alone nature of the office makes certain potential pitfalls very simple to avoid. To implement a system for something like a presidential election that manifests any kind of gerrymandering-adjacent issues, takes… effort (I’m looking at you, US Electoral College). Just because some countries fail to meet even this very low bar doesn’t mean that we can’t set the bar higher.

In a straightforward vote to determine the winner of a single office, the main thing standing in the way of getting a leader that best represents the interests of the electorate is tactical voting. Any vote with more than 2 options is open to tactical voting, but there are some forms of tactical voting that are more pathological than others. A bad voting method will provide perverse incentives that result in people that support a particular candidate voting for someone they support less, or not voting at all.

The really problematic issues that voting methods could have, that it would be good to avoid are the following:

- Being a dictatorship

- This one is obvious – if there is someone whose vote always determines the winner, it is de-facto a dictatorship, not a democracy, so this is a pretty undesirable quality

- A voting method that avoids this is referred to as a “Non-dictatorship“

- Permitting only one axis of satisfaction

- Imagine an election between four candidates with the manifestos:

- “Crush our enemies, save the environment”

- “The best defence is a good offence, tax polluting industries”

- “Avoid conflict, stop worrying about the climate”

- “Get rid of the military, burn the forests”

- Despite the presence of two very different issues, these four candidates are on a single axis from one extreme to the other

- There is no party for non-interventionist environmentalists or for interventionist industrialists

- A voting method that permits any combination of preferences is referred to as having “Unrestricted Domain“

- Imagine an election between four candidates with the manifestos:

- Changing the winner when an additional unpopular candidate runs

- Clearly if an additional candidate is very popular, they could win the election, but if the additional candidate isn’t going to win, their presence in the election shouldn’t change who does

- A good example of this from the sporting world is the 1995 women’s figure skating world championships, in which the performance of the fourth place finisher resulted in the competitors in second and third switching places!

- This phenomenon also includes the “Spoiler Effect“, in which a candidate splits the vote of the candidate that would have won, resulting in the second most popular candidate winning instead

- A voting method that is unaffected by the presence of irrelevant candidates is said to have “Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA)“

- Declaring a victor that voters unanimously rated worse than another

- If all voters prefer candidate X over candidate Y, the voting method should not result in candidate Y doing better than candidate X

- A voting method whose result always preserves unanimous preferences is referred to as “Pareto Efficient“

- Reducing a candidate’s performance when they get more votes

- If the act of voting for a candidate, or ranking them higher causes them to perform less well, this is clearly a perverse incentive that could discourage people from voting honestly

- Equally, being able to improve a candidate’s chances by voting against them is a problematic tactic to encourage

- Despite its simplicity, the Single Transferable Vote method can result in situations where this occurs

- A voting method in which support will never harm a candidate’s result is referred to as “Monotonic“

(Site note: there are criticisms of having IIA as a requirement of a voting method, insofar as it is in direct opposition the Majority Criterion (that if a candidate is the favourite of a majority of the electorate, then this candidate will necessarily win). Whilst the Majority Criterion sounds like an obviously desirable quality of a voting method, it is worth considering the issue of Tyrrany of the Majority alluded to earlier. A compromise candidate that is not the majority’s absolute favourite, but that has the support of an even broader section of the electorate is generally going to be less partisan and more of a unifying force. This makes the Majority Criterion actually not such a “no-brainer”.)

So, having decided on a very reasonable set of minimum requirements to have for a voting method, so that we avoid obvious failure modes and perverse incentives what are we left with?

Well… Not much actually! It turns out that it can be mathematically proven that it is impossible to design a ranked preference voting method that satisfies all of Non-dictatorship, Unrestricted Domain, IIA, Pareto Efficiency and Monotonicity. This is known as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, and it is indeed most disappointing.

Cardinal Virtue

Do we now give up and go home? Is how we decide our leaders doomed to be hopelessly broken in some way? Not quite yet. There is a glimmer of hope in the previous paragraph where the statement of Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem includes the words “ranked preference voting method”.

A large number of voting methods involve people ranking the candidates in order of their preference, so they pick who their 1st choice is, who their 2nd choice is, and so on. You can’t rank multiple candidates as 1st, even if you consider them indistinguishable. These are also known as “ordinal” voting methods, and for a long time, this was the default assumption when people were trying to find ways to improve how to reflect people’s wishes through voting.

There is another way however – “cardinal” voting methods are ones in which you give candidates a score which doesn’t have to be unique. Giving a higher score to a candidate means that you prefer them – simple! This change in approach means that Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem no longer applies, which is a huge win.

So which voting methods does this leave us with? For the kind of single winner elections we are looking at here, there are a few alternatives:

Range Voting (or Score Voting) involves giving voters a range of scores that they can give to candidates – perhaps 0–4, 0–10 or even -100–100, then allowing voters to give all candidates a score in this range. These scores are then added up, and the highest scoring candidate wins. A good summary of Range Voting and its nuances can be found here.

Approval Voting is really just Range Voting with a range of 0–1. You can either approve of a candidate or not. This does inevitably reduce the amount of information a voter can give the voting system, but it has the advantage of being much easier and simpler to implement. You can use the same voting slips as are used for current “first past the post” elections, but people can put a cross in as many boxes as they want. There is in fact a charity in the US aimed at promoting Approval Voting, whose website has more information about its benefits.

Majority Judgment is similar to Range Voting but instead of summing the scores and picking the highest scoring candidate, the candidate with the highest median score wins instead. This has the effect of discounting extreme outliers, making certain types of tactical voting less effective, but with the cost of making the process slightly less simple and understandable.

[edit]

STAR Voting stands for Score Then Automatic Run-off. This is Score/Range voting in which all but the top two candidates are eliminated, then the winner is the candidate with the most ballots scoring them higher than their opponent. This method has demonstrated resistance to tactical voting in simulations, though the introduction of an automatic run-off actually results in this method still failing IIA.

Unfortunately for Majority Judgment and STAR, they both fail a couple of other very reasonable criteria that have not been mentioned yet, as they are not covered by Arrow’s theorem:

- They both fail the Participation criterion, which means that there are situations in which voters can do better by not voting. This is not quite as bad as non-monotonicity, but it is a very similar problem that could make the methods appear undemocratic.

- They both also fail the Consistency criterion, which means that if the electorate is split into parts, even if all of the parts have the same winner, a different winner can be elected by the combined electorate. This could lead to some very confusing maps being produced that shake people’s faith in the legitimacy of their democracy.

[/edit]

Reliability

With all of these cardinal methods, it is still permissible to vote for a single candidate, if that is the only candidate you approve of. Equally, if you approve of all but one candidate you can vote for all but one (in the case of Approval Voting, this has the same effect as cancelling out one vote for that candidate). Anything between these two extremes is completely fine too, allowing you to not worry about “wasting a vote” on a small party that doesn’t have much chance. This should allow people to vote with their hearts much more, reducing the stranglehold that two-party systems have over most “first past the post” democracies.

Of course, it is important to note that this doesn’t completely remove tactical voting. In fact, Gibbard’s Theorem states that there will always be possible scenarios in which tactical voting can be beneficial to voters, so cardinal voting methods are not immune. For example, Burr’s Dilemma is a potential issue that could still arise if two quite similar candidates are also frontrunners, though there are hardly any examples of this occurring in practice. Large numbers of voters practicing tactical voting in a Burr’s Dilemma type situation will break IIA, because even though voters’ opinions shouldn’t change, the tactics being used change depending on which candidates are running.

Range Voting and Approval Voting do however satisfy all of the conditions above when people vote honestly – Non-dictatorship, Unrestricted Domain, IIA, Pareto Efficiency, Monotonicity, Participation and Consistency. This means that you are never punished for participating (voting for your candidate can’t hurt their chances), and the spoiler effect is avoided for minor candidates (there is no vote-splitting, unless the “spoiler” themself is a major contender, leading to Burr’s Dilemma style tactics). This should reduce political polarisation by making voting for centrist parties more attractive, as well as increasing engagement by making voting for niche parties more attractive too.

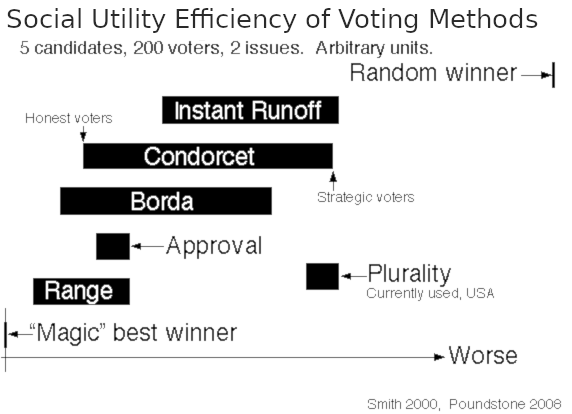

All of this makes these methods significantly more reliable than most other voting methods for actually capturing the preferences of the populace. The graph below shows the hypothetical outcomes of 144 simulated elections, where the outcome is measured by the average satisfaction the electorate has with the election winner (known as the Social Utility Efficiency or Voter Satisfaction Efficiency):

(Side note: for Approval Voting, Range Voting and Majority Judgment to satisfy the IIA criterion, it is assumed that voters’ individual scores themselves are also independent of irrelevant alternatives. This assumption implies that in an election with only two candidates some voters might vote for both (or neither), which would be a vote that had no effect. I am inclined to think that this is completely reasonable, after all plenty of people currently choose not to vote because they don’t approve of any of the parties. Further to this, in the case of only two candidates, most of the issues that plague voting methods are avoided anyway, and many different methods become equivalent to each other with only two candidates in the running. Finally, part of the benefit of these particular voting methods is that they encourage more than two candidates to run, so this situation should not be the norm.)

Recommendation

Of the cardinal voting methods discussed, I am personally inclined towards Approval Voting for these purposes, due to its greater simplicity and familiarity when compared to current ballot papers. Nicky Case’s website has a brilliant, interactive introduction to voting methods, the issues with ranked voting and the benefits of Approval Voting. Even if you are already quite familiar with the issues discussed here, I highly recommend checking it out.

12 Replies to “Voting Systems – Electing Leaders”

Nice article. A few notes on terminology:

“Voting system” has an ambiguous meaning. It can mean hardware and/or software; it can mean a mathematical algorithm, as you’re using it in this article; or it can mean the entire set of laws and procedures of a given jurisdiction around voting, which includes both of the former meanings but also things like rules about who gets to vote and when. Thus, “voting method” is a better word, because it unambiguously means the algorithm.

“Bayesian regret” is also a poor term. Rev. Thomas Bayes was indeed a utilitarian philosopher, but he’s mostly known today for his theorem on conditional probabilities; “Bayesian Regret” has nothing to do with conditional probabilities, only with expected value. Thus, the more-current term for “Bayesian Regret” is Voter Satisfaction Efficiency, or VSE: http://electionscience.github.io/vse-sim/VSE/.

You do a good job explaining ordinal and cardinal voting methods, but you don’t mention hybrid methods such as STAR voting or 3-2-1 voting. Although these hybrids forego the provable perfection of either side on certain criteria, in practice it’s been shown they can pass the criteria more often in practice. I believe it’s better to almost-always pass two good criteria than to always pass one but often fail the other.

Jameson:

Bayesian Regret is the term that’s in popular use to describe the phenomenon, whether or not you disagree with its naming: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayesian_regret

https://rangevoting.org/BayRegDum.html

“You do a good job explaining ordinal and cardinal voting methods, but you don’t mention hybrid methods such as STAR voting or 3-2-1 voting.”

Systems with automatic runoffs have known flaws compared to Score Voting, including STAR: https://rangevoting.org/StarVoting.html

STAR voting is not worth bothering with. While significantly better than most other election systems (Borda, IRV, FPTP), it adds an unnecessary layer of complexity to Score Voting that, instead of improving anything, adds several significant potential flaws to the system, including cases of non-monotonicity.

STAR is being popularized not because it’s superior to Score Voting (it’s not) but because there’s been an active campaign from places like FairVote to push for the near-useless IRV method whilst poisoning the waters and actively putting out falsehoods and propaganda about the evils of Score Voting (which have been dismantled thoroughly and repeatedly). STAR is seen as a way to promote Score Voting as a way that’s different enough to be seen as sexy, new, and exciting, while avoiding previous negative propaganda tied to Score Voting.

I am on the board of directors of the Equal Vote Coalition, the primary umbrella organization supporting (among other reforms) STAR voting. So I believe I know why STAR is being popularized. And it is indeed because we believe it is better than score voting. That “we” includes me; with a PhD in statistics, ex-board-member of the Center for Election Science, co-organizer of the British Columbia Symposium on Proportional Representation, inventor of the EPH voting method used by the Hugo awards, consultant on voting methods to the Webby awards, co-author with Bruce Schneier of a peer-reviewed paper on voting methods, and having carried out further research (both monte-carlo and mechanical-turk-based) on voting method quality.

You are free to disagree about whether STAR is better than score. But please do not misrepresent the facts of why it is being promoted. We, its promoters, have evidence that it has much better resistance to voting strategy than score voting and I think it’s clear that it would thereby lead to better outcomes in practice.

I’m glad you enjoyed the post.

I didn’t include analysis of STAR because it failed IIA, however I can understand why some people don’t consider this a deal-breaker – the fact that tactical voting can make cardinal methods fail IIA does reduce the impact of the failure somewhat.

Perhaps I wrote it off too quickly and didn’t do it justice.

There are a few more disadvantages to STAR though:

1. Although the monotonicity criterion is not failed by STAR in a technical sense, the situation hhh links to above is nevertheless quite counter-intuitive, and looks quite like non-monotonicity

2. It fails the Participation criterion, so people could be better off if they didn’t vote (as does Majority Judgment)

3. It fails the Consistency criterion, so if the electorate is split into parts, even if all of the parts have the same winner, a different winner can be elected by the combined electorate, which could lead to some very confusing maps being produced that shake people’s faith in the legitimacy of the method (again, Majority Judgment has this issue too)

4. It is a significantly more complicated method than Approval or Score voting for both voters and vote counting

Fundamentally, the “automatic run-off” seems to introduce the possibility for quite a bit of strange behaviour.

Your comment states that STAR performs better when people vote tactically, but hhh’s link suggests that >75% of voters must be voting tactically for this to be the case. In the presence of such levels of tactical voting, its tactic-resistance may well outweigh the disadvantages above, but such high levels of tactical voting sound quite unlikely to me.

I would be interested in any evidence or studies showing that either:

a. STAR outperforms Approval or Score voting with levels of tactical voting <75%

b. The proportion of people that would vote tactically under Approval or Score voting is greater than this threshold

It is possible that I could get behind the idea of score voting being used for a “primary”, with a separate vote for the final 2 run-off (in a similar way to the French presidential elections 2-round system). Making the run-off election a completely separate vote appears to avoid a lot of the strange behaviour of STAR whilst maintaining the tactic-resistance. This would be more expensive and complex, but that could be justifiable for something like a presidential election.

You are clearly someone that has looked into this in great detail, and some evidence/study/simulation/experience has convinced you that the benefits of STAR outweigh its drawbacks. I would be very interested to know what that is, as to me the combination of complexity, failing IIA, failing participation and failing consistency give it a very high barrier to overcome.

I have now edited the post to include a couple of paragraphs on STAR Voting, using some of the points above.

“I would be interested in any evidence or studies showing that either:

a. STAR outperforms Approval or Score voting with levels of tactical voting <75%

b. The proportion of people that would vote tactically under Approval or Score voting is greater than this threshold"

I can only really address b) but some info with regards to Score Voting and honestly (or rather how Score Voting encourages honesty):

https://rangevoting.org/HonestyExec.html

Points 8 and 8 will be of particular interest ("And even when voters do choose to vote strategically in range voting, the consequences are mild, even pleasant").

There's even a page detailing evidence that suggests you can expect a good number of honest and strategic voters in any election (including honest but "stupid" voters in the sense that they appear to value honestly without realizing it's going against their own political interests!): https://rangevoting.org/HonStrat.html

This suggests that Score Voting will perform well for honest voters as they're less likely to inadvertently hurt themselves without realizing it, without being too seriously affected by strategic voting. Indeed, if most people (say above 75%) are voting strategically (min/maxing scores) then at worst Score Voting will perform akin to Approval Voting, which is also known to be a very decent method in its own right.

Since you linked it, the Wikipedia page you linked no longer has a section on voting theory. You can see the talk page ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:Bayesian_regret#Not_an_accepted_term_in_voting%2Fsocial_choice_theory ) for a discussion of why not.

(I am being cagey about who made that edit for reasons of anonymity but I am not trying to hide the obvious conclusion.)

Thanks for the heads-up – I have changed the image to avoid further confusion.

(“Bayesian Regret” is not a term I actually used in the above post – it is simply in the title of the graph that was taken from Poundstone’s book, which is so titled because it is referencing Smith’s work.)

Since this misnomer is nonetheless in use, I would suggest that rather than leaving the Bayesian Regret Wikipedia article with no reference at all to this usage, it might be better to link to the article about the actual term that is used:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_utility_efficiency

Something along the lines of “The term Bayesian Regret has been used to refer to the concept of average probabilistic regret in Social Choice Theory, however this is something of a misnomer as it has little to do with updating priors. [[Social Utility Efficiency]] is the preferred term.”

I note that this article is linked in the “See also” section, but without context. This might not be sufficiently obvious or helpful for people looking into the term having read Poundstone’s book or Smith’s papers. It would be good for people to be able to easily find out the actual term that is in use, rather than hitting what looks like a dead end.

You’re forgetting one of the most powerful democratic techniques. Random selection or sortition.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sortition

Random selection is a very powerful technique, similarly to why random sampling is such a powerful technique used by modern science & statistics. Random samples tend towards representative samples.

Funny you should mention that – I haven’t forgotten sortition at all, I’m just saving it for a later post.

This post is specifically about selecting individual leaders, for which sortition isn’t really suitable. A lot rests on the shoulders of a president/governor/prime minister, and it probably wouldn’t go well to just hand that job to a random person. On the other hand, if you are talking about selecting multiple candidates to represent a population, this is somewhere sortition could be very useful indeed. You might have to wait a couple of weeks, but I will cover this!