In Support of Federalism

This post follows on from Legibility and Democracy.

Finding the best way to govern a country is an ongoing struggle throughout the world. The introduction of the concept of legibility suggested that federations might be a good middle ground providing both legibility and democracy for the electorate. Widening the scope beyond this, there are many other advantages of federations over unitary states.

Antifragility

In Nassim Taleb’s book “Antifragile”, he repeatedly praises federal countries especially Switzerland for their antifragility. This is an even stronger concept than mere robustness – federal systems with semi-autonomous states not only withstand uncertainty and disruption, but can actually benefit from it. A federal system allows different policies, systems and approaches to be tried out. If a system is poor, the state implementing it will perform poorly, but it should not have too much of a wider impact on the country as a whole. The state can then revert to a previous system or adopt a more successful one tried by a different state. It is through this natural experimentation and repeated divergence and reconvergence of policy that obstacles can be overcome, and large improvements can be made.

In extremis, the federal government can provide assistance to get the state back on its feet. In the event that an adopted policy risks causing catastrophe, this fallback should avoid any truly egregious humanitarian cost, but again the catastrophe should be fairly localised to the relevant state, allowing other states to learn from the experience without going through it themselves. Ultimately, if a system is an improvement, other states are likely to gradually adopt it, but allowing states to do this gradually rather than enforcing it through a centralised unitary system of government allows any kinks to be ironed out and any unforeseen consequences to be explored, without people feeling like they’re being experimented upon by the government.

Freedom

In some circumstances you might expect certain laws to diverge and stay that way – certain communities may like to do things differently, and if that attracts more like-minded people, you can end up with a stable set of laws for one state that are quite different to another. This variation between states, combined with free movement between the states means that people can vote with their feet as well as their ballot, providing another form of feedback as to which laws are beneficial, as well as giving people greater freedom than the single set of rules handed down by a unitary government. This goes some way towards the “Archipelago” idea of Scott Alexander (Archive).

The ideal situation from the perspective of freedom, is of appropriate governance at the appropriate level – pushing down power and responsibility to the lowest level of government that can effectively wield it. This reduces the power of higher levels of government to what is necessary to keep the lower levels functioning well, and is antithetical to the functioning of a highly centralised government. Of course, smaller units may lack necessary expertise, so things shouldn’t be pushed down to a level that is too low to be effective.

A good example of the idea of “appropriate governance at the appropriate level” is zoning laws – the US often sets restrictions on what kind of buildings can be built at a very local level, resulting in small municipalities lacking the expertise in urban planning to set sensible regulations. This leads to rules that may seem simple to the regulators, but that result in highly inefficient city layouts requiring everyone to have a car just to go to the shops. In contrast, zoning in Japan is done at a national level, which allows them to leverage the experience and expertise of specialists to create slightly more complex but flexible rules. This is not to say that this in particular should be done at a national level – it could be done at a state level if the size of the state were sufficient to enable it to maintain this expertise, but it is a good example of something that the US may have delegated too far.

Political Incubation

In a large country, it can be difficult for anyone to rise to prominence – with no pre-existing smaller structures to gain traction with, prominence and recognition is very much based on either luck (“going viral”) or money (to pay for adverts and exposure). Whilst this is very much a reality for artists and performers, it is also often the case for politicians, who naturally operate in a divisive and polarised “winner takes all” environment. A performer may find a sustainable niche with a small number of avid fans, but the spectre of unelectability dooms any politician that cannot break into national prominence. Too much luck or wealth based success winnows the pool of eligible candidates prematurely, resulting in less skilled and effective politicians, and less choice for the electorate.

On the flip side, rising to prominence in a smaller state is easier – statewide advertising is cheaper than countrywide advertising, and it is only necessary to be electable locally to be able to survive. Doing a good job locally will allow a politician to generate a positive reputation and wider appeal, rather than relying on a lucky break. One could argue that a country’s legislature is often made up of local representatives, however these positions necessarily take the politicians away from their local area, and require them to wrangle with national issues that are often divorced from their constituents’ everyday lives. Few people in the UK can reliably remember who their MP is, so it does little for their prominence. State governorship however is something that affects people on a day to day basis more than the concerns of the federal government, so a governor or mayor will be more relevant and recognisable to their constituents. This kind of role also provides politicians with executive political experience at lower stakes than the national stage, giving a wider field of experienced candidates for people to pick from when it comes to national elections.

Proximity to Capital

Politicians usually need to be physically present in the Capital. If this is too distant from their constituents, it becomes more difficult to spend time with the people they are supposed to represent, so they can become out of touch. Once they are spending the majority of their time far away in the Capital, it is very easy for them to lose focus on the issues that are important to their constituents, and possibly to even fall into groupthink with the other politicians. This can lead to areas being underrepresented or neglected, and to undue attention and funding being given to the areas that politicians do frequent, namely the Capital and its surroundings.

Alternatively, if they spend too long away from the Capital, ensuring they have a strong link to their constituents, they will not be “in the room” for important decisions and will therefore not be able to represent them as effectively. This can again lead to underrepresentation of areas, and a sense that the government is actively ignoring the needs of certain groups.

Easy access to the Capital for the general public is also beneficial to the democratic process. This can take many forms, but at the very least close proximity is helpful for protesting against or demonstrating for particular policies. The further away the seat of power is from people, the less they will be able to be physically present, and therefore the less empowered they will be.

Many of these issues have historical parallels, even right back to the Roman Empire. Slightly different problems to those of a modern democracy, but the principles are remarkably similar. The difficulties of governing a large area from Rome was a factor in several civil wars, and was what drove Diocletian to split the empire into four, with a tetrarch governing each area from their capitals of Milan, Trier, Sirmium and Nicomedia.

Once Constatine reconsolidated the empire and moved the capital to Constantinople (modern day Istanbul), the east of the empire was able to be stabilised. This allowed it to persist for another millennium as what we now call the Byzantine empire, but the empire quickly lost control of the western provinces which were too far from the seat of power to maintain effective control over.

With a federal system, although there is still a national capital, there is so much that is devolved to the states that there is a local power centre within each state that allows people easier engagement with the democratic process. This means that although Washington D.C. receives many complaints in the US, there is much less concern about the government being “Washington-centric” than there are concerns about the UK government being “London-centric”.

Economic Stability

We can extend this proximity argument to economic concerns as well as democratic ones. In the UK, London receives more funding and more attention than most other areas, and it is hard to argue that this is not at least in part because the politicians are physically there, witnessing issues firsthand. Other areas of the UK that are comparatively neglected are simply not seen by enough of the politicians for their problems to be taken seriously.

As well as leading to public dissatisfaction and rhetoric about out-of-touch “metropolitan elites”, this unbalanced attention and funding actually exacerbates the problem more. The Capital will grow and prosper, while other areas decline, giving more people and businesses a reason to leave the declining regions and move to the Capital. This vicious circle then seems to justify the unbalanced attention – most economic growth will stem from the Capital, so the Capital is seen as “a much better investment” by the government.

Within a federal country, state governments are necessarily spread throughout the country. This both incentivises the state governments to resolve issues within their state, and provides local employment. The presence of government functions in a region guarantees a base level of economically active people in that area that other companies and people can rely on. This reduces the likelihood of an economic downturn spiralling into a mass exodus from a particular region, by providing acyclical employment.

Another economic effect that federal systems introduce is the ability of states to negotiate with the central government to get further civil service jobs or federal level agencies based within their borders. This can be seen as a negative, often called “horse trading” and “pork barrel spending”, but it encourages critical functions to be spread out, both making them more robust, and ensuring that economic windfalls are not concentrated solely in the Capital region.

The US does this a significant amount, for example NASA has the following sites across the US:

To its credit, the UK has spread some of its government employment around (the DVLA in Swansea, HMRC in Cumbernauld, etc.), but it is much more able to change this on a whim. Without a political entity able to argue against a removal of jobs from a region by the central government, this employment is less geographically reliable, and could easily be uprooted by successive governments.

Conflict Resolution

We can see from recent conflicts that attempted to “export” democracy, that states that have had democracy imposed on them in a top-down fashion can be very unstable. Aside from the inevitable instability induced by this imposition, there is a tendency for such top-down imposition to be done without reference to the existing local systems already in place. By bypassing existing local systems and structures, whether they are clans with elders or congregations with religious leaders, the local institutions have not bought into the project and may work to undermine it. These local systems have been around for much longer and have greater loyalty and legitimacy than the newly imposed democracy, so people are unlikely to suddenly feel a connection to the elected central government. An example of a nascent democracy that is currently in between the “democracy for elders” stage and full democracy is the breakaway region of Somaliland.

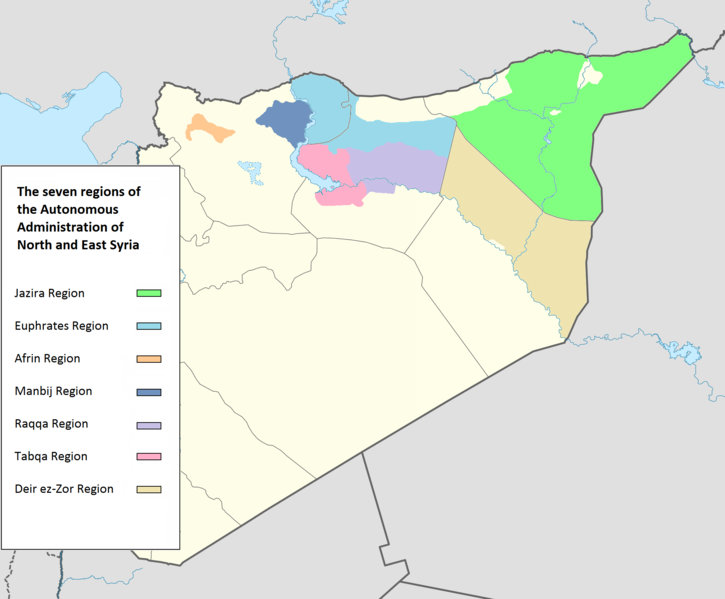

Although it is not the only way to end up with a democracy, many stable democratic regimes have started with local institutions. Even where these local institutions are not democratic themselves, their leaders are likely to try to engage with each other on an equal footing, to avoid subservience. This can lead to the creation of larger institutions that are fundamentally democratic in character (even if it is only the local leaders that get a say). Eventually, if the democratic nature of these larger institutions is observable, it could lead to movements to democratise the local institutions themselves. Whilst not necessarily always strictly “federal”, this concept of bottom-up progress towards democracy seems to be possible with much less intervention (and given the examples of Somaliland and Rojava perhaps sometimes with no intervention at all).

In a nascent democracy, the ability of states to govern independently from the national government also reduces the risk of a government trying to subjugate minorities. After decades of oppression, the Kurdish minority in Iraq have achieved a degree of autonomy through the federalisation of Iraq that was written into their constitution in 2005. The political autonomy that federalism provides, with some control over their own budgets and rules, ensures that the central government will find it much harder to oppress this minority in future.

In a similar way, the collapse of Yugoslavia demonstrates a failure mode of federalism. Whilst “balkanisation” is often seen as something to be avoided due to the continued violence in the region after the collapse, the ethno-religious conflicts that it exposed were present in Yugoslavia long before its fragmentation. This fragmentation can actually be viewed in a positive light – the direct result of a heavy-handed national government trying to limit the independence of its federal subjects. In this scenario, if a federation must fail, the two most likely outcomes are that the federal government succeeds in centralising authority, or that the individual states secede to become independent countries. Had Yugoslavia been a centralised state already, any fragmentation would not have had such natural fault lines, and the states would not have had existing governments, making fragmentation much less likely. In this scenario, the lack of fragmentation simply allows the central government to continue to oppress minorities – it may be less visible, because it would be a “domestic issue” rather than a war between countries, but it is likely to have a far worse humanitarian cost.

With the modern status of “nation states” being the default unit that individuals, organisations and countries interact with, it is very easy to either ignore or underplay conflict that is internal to a country. When South Sudan seceded from Sudan, it suddenly became apparent how much poorer and more deprived this region was, when this had previously been obscured by aggregated national statistics. Federalism formalises a structure that reduces the ability of a central government to run roughshod over the rights of some of its citizens, or to simply neglect them, reducing the risk of “Tyranny of the Majority”.

Alternatives

Countries do not have to be either federal or highly centralised – there are a couple of other systems of government that can be considered. These are confederation and devolution, and it would not be a complete discussion of the benefits of federalism without considering them as well.

Firstly, a confederation is a weaker political union than a federation that explicitly allows secession. This is good for countries organically coming together to form alliances (eg. the European Union), but it is unlikely to be politically viable for a country itself, as this would facilitate the country potentially losing territory without the need for a complete collapse of the central government. Governments can of course at any point decide to cede territory, but as with the Scottish independence referendum, this is an active decision on behalf of the central government. In a confederation, there is legal provision for a state to unilaterally secede, which has the potential to be far more disruptive.

Although there are some countries that refer to themselves as confederations, there are no real confederations currently, with the exception of the EU and possibly Rojava. Looking at the range of countries that have been confederations at one point or another, it seems more of a transitory status of a group of countries either joining together or splitting apart. All confederations have historically eventually ended up either forming federations (eg. Switzerland and Argentina) or splitting into separate countries (eg. the United Arab Republic and the Greater Republic of Central America.

Secondly, devolution is a way for a central government to gain some of the benefits of federalism, by giving certain powers to sub-national administrative divisions. In many ways devolution can serve the same purposes as a federation – if the appropriate governance is devolved, this can be virtually indistinguishable from a federal state for the citizens.

The top level government however always retains the power to legally overrule the devolved governments, and change the devolved powers unilaterally. This makes the system less robust, being more prone to failure if the central government is compromised. Structural change can be made more rapidly when a devolved country is not federalised, which might sound positive, but is actually another source of risk. The central government can enforce adoption of certain policies by all provinces, reducing the “different systems, different approaches” antifragile benefit. Rapid systemic changes are always dangerous, and although a federation might take more time to implement a beneficial change, their ability to avoid large changes that turn out to be mistakes is a key feature of the system.

Over the short term, if a state is currently highly devolved, it can be reasonably compared to a federal one, but this status can change at any time at the whim of the central government. With a federal state, the federal nature is very difficult to change, so more likely to endure through the tenure of a federal government that is keen to centralise.

Common Factors

Some of the benefits of federalism listed above centre around different cultures having autonomy to set some of their own rules, avoiding a “one size fits all” approach. Others are fundamentally related to the fact that regardless of the size of the country, states can be an “appropriate” size. Large enough to support a functioning government, but small enough for people to feel like their voice matters. Large enough to have clout with the federal government, but small enough to be allowed to experiment – not “too big to fail”.

These factors suggest that there might be an optimal configuration for any particular country, or at the very least a range of directions in which the configuration can be improved. Federalism on its own might not be enough to deliver all of these potential advantages – there might be a particular size of state, or method of administration that makes these advantages more likely to materialise. It is these considerations that I intend to delve into in the next post.

5 Replies to “In Support of Federalism”

Federations, such as Greek city states, Hansa and the Dutch republic, have been generally much more prosperous than the cotemporary societies with centralized governments. However, they tend to be vulnerable to external aggression. For example, during the first Anglo-Dutch war the Dutch republic possessed much bigger economic resources than the post-civil war England. The Dutch still lost, as its inland provinces were not fully committed to the fight and the English government was more effective in mobilizing its resources. There are similar examples in the conflicts between the French kingdom and cities of Northern Italy, Greek cities and the Macedonian kingdom, Hansa and the kingdom of Denmark.

Federations are also vulnerable to their own central governments which over time concentrate more and more powers in their own hands. Perhaps the most difficult question is how can the centralized government be made to give up its powers in favor of local authorities. Do you see a realistic way of this happening in the UK?

A very good point. It is a difficult balance between avoiding a federal government overriding the states’ autonomy, whilst keeping certain functions centralised and coordinated.

Many modern federations do at least have a significant portion of their revenue generation that is highly centralised and federally managed, which ensures that “resources” shouldn’t be too much of an issue. The military is generally also a federal function, which is sensible, as this enables centralised mobilisation.

With these being the modern status quo, I think the ability of federations to defend themselves and project force in a coordinated manner shouldn’t be too much in doubt. Your second point is therefore probably the most salient one – how do we limit the power of federal governments to avoid them concentrating power over time?

I have a few thoughts on how to modify the structure of government to reduce this (and improve it in other ways), that I’m going to hopefully delve into in the next few posts. One (fairly radical) is around sortition, that I mentioned in last week’s post as a way to reduce the perverse incentives of the political class to resort to populism. Another is around improving on the presidential and parliamentary systems – I am a big fan of the “separation of powers” between the legislature and executive, as parliamentary systems that don’t have this are too easily able to force through laws to allow them to do what they want, but presidential systems concentrate too much power into one individual. A system in which the entire executive cabinet were directly elected would avoid both of these problems – keeping separation of powers, whilst spreading executive power between multiple (equally powerful but department specific) people. At this point, I have half written posts about both of these, so I’ll hopefully post something on them soon.

In terms of how a centralised government might be convinced to give up power to local authorities, I think there is a way. Ultimately, governments are made up of individuals, so if you can make something beneficial to enough of the individuals, they may vote to “reduce the government’s power”, because it is still increasing their own power or status.

The UK currently has 650 MPs, so in a hypothetical federalisation of the UK in which you reduce the “federal parliament” down to 250 MFPs, and split the UK into 20 states that each have state assemblies of 20 people each, you still need 650 politicians in total. Many politicians that think they will end up winning as a new MFP will be keen on the plan, as they will be 1/250 rather than 1/650, so despite the reduced scope of the federal parliament, they will have more power within it (and the federal parliament gets all the “sexy” stuff like foreign policy…). Similarly, many other politicians will be interested to be a “big fish in a small pond” – rather than being 1/650, these politicians will be only 1/20. If the new powers that states will gain are the functions of government these particular politicians are interested in (education, healthcare, etc.), many politicians might jump at the chance to have a greater sway in their management.

Basically, because different politicians will have slightly different focuses and motivations, it should be possible to create a system where everyone feels like they’re winning – everyone gets to be a bigger fish in a smaller pond that is more relevant to their interests. There will always be some people that don’t want change, but if you can get a majority to support it, you’ve won.

if you can make something beneficial to enough of the individuals, they may vote to “reduce the government’s power”, because it is still increasing their own power or status.

True, but I suspect most MPs might not see this change as a net benefit:

1) Any major shakeup of the electoral system increases the chances of outsiders. So, the chances of 400 MPs who lose their seats to be elected to state assemblies would probably be lower than their chances to be reelected to parliament under the old system.

2) The change would be viewed as a loss by the PM, cabinet ministers and those who have a realistic expectation to get these positions in the future (i.e. politicians who are far more influential than an average MP).

3) Most MPs might not like having to move their families from the capital to less glamorous places.