Doing Things Differently – Adventures Raising the Next Generation

Introduction

It has been some time since I posted on this blog. Writing posts that are good enough for me to consider posting takes a reasonable amount of effort, and since my last post I embarked upon a new project that significantly reduced my time available to work on such things. Given the title of this post, it will come as no surprise that the new project in question is “everything associated with having and raising a child”. This project is probably of limited interest to some, but there are aspects of the experience that I feel that I should share, in case it is of benefit to others.

By “doing things differently”, I refer to the process of questioning why an approach to something may be the norm, and choosing an alternative path that is more optimal (for me at least – other people’s predilections may differ). This of course carries risks, and I try to think through as many reasons why the norm is indeed the norm, before I cavalierly leap over Chesterton’s fence. However, if after this process, I still feel that I can make my life easier/better/more efficient with minimal risk, then I give the alternative approach a try.

I had been planning to do a post at some point about general successes (and occasional failures) that I have had in doing things differently in life. While I may yet do this, the specific situation of having a child yields more than enough material for its own dedicated post. My inclination to write this post has grown gradually as I encounter more and more people that are on the fence about whether or not to have children.

The vast majority of media that I am witness to portrays parenthood as a thankless slog through sleepless nights and ego death which is justified by the platitude that “your love for them makes it all worthwhile”. On this basis, it is quite unsurprising that people are in two minds about the decision, and this has to be a contributing factor in the rapid global decline in fertility that Robin Hanson has recently been taking very seriously.

I can quite happily say that so far this is not my experience at all, however I have taken some unconventional approaches, which may have made a significant difference. I went into this process with very low expectations – I was fully prepared for at least two years of hell, and the experience has been so much better than my wildest hopes that I can’t help but feel that we must be doing something right. I really don’t identify with most of the sad tropes about stressed out miserable parents. This drives me to want to share these approaches and my reasoning behind them, as they have been very successful for us, and may give other people ideas for how to make the experience work better for them.

Of course, some people may not be in a position where they can do some of these things – for example, I am based in the UK where taking parental leave is a legal right, whereas people in other jurisdictions may not be able to (the US – I’m looking at you). I must also further caveat this with “your mileage may vary” – I am currently operating with a sample size of 1 and all babies are different.

Nevertheless, there are a large enough set of “weird” or unconventional things that we did, that some of them may be of some use, so if any of these approaches sound reasonable to you, feel free to take them. This is a long article, so feel free to skip to any section that looks particularly interesting, but the ones that have been the most game-changing and foundational to our approach are 1 and 11.

- Concurrent Parental Leave

- Sleeping in Shifts

- Combi Feeding

- Baby Carrying

- Taking a Long Holiday with the New Baby

- Sign Language

- Elimination Communication

- Baby Led Weaning

- Having a Flexible (and Late) Routine

- Floor Bed

- Both Parents Working Part-time

- No Screen Time

- Books and Letters

I am not trying to claim that we’ve invented anything new – I don’t doubt that we’re not the first people to have done any of the things described here, but even over 2 years in, I have yet to meet anyone that has done any of 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 or 11. I am also not trying to claim that we have done absolutely everything perfectly. While I am pleased to say that there are very few things that we would do significantly differently next time around, we were still learning as we went along. Reading books can only get you so far, and at a certain point, we had to resort to trial and error to find what worked the best for our child as an individual.

Finally, I repeatedly say “we”, because I have been doing all of this together with my partner. She has not just been supportive and enthusiastic about some of my unusual ideas, but has come up with plenty of unusual ideas of her own. Neither of us can take sole credit for any of the approaches below, as whilst either of us may have made the original proposal behind any particular idea, we have collaborated on all of them to make them work. She has also read this essay and agrees with the sentiments expressed herein, so before anyone decides that “of course you have found it a positive experience, you’re a man – your partner is the one doing all the hard work”, I would like to address that trope head on. We both try very hard to maintain an egalitarian relationship, and that is what initially drove us to take approaches 1 and 11, which have gone a long way towards helping us to avoid many of the common pitfalls of inequality in parenting (e.g. mother as default parent, learned helplessness and maternal gatekeeping, underappreciation of domestic/emotional labour, etc.).

With all that out of the way, let me get on with sharing our approach.

Concurrent Parental Leave

The first unusual thing that we did was to both take parental leave at the same time. We each took 6 months off concurrently. This was absolutely great, and I would recommend it to anyone that asked (as long as they were in a sufficiently comfortable financial position to utilise the full 52 weeks). We will definitely be doing the same thing next time.

In the UK, you are entitled to 52 weeks of parental leave, which can be split however you like between the mother and father. Uptake of this “shared parental leave” has been very low with only 2% of fathers making use of it, however in the cases where people have made use of it, most people take it sequentially, with the mother taking off the first 6 months and the father taking the last 6 months, or 9 and 3 months, etc. A majority of the people that we have spoken to were not aware that the leave could be taken concurrently.

Although taking the leave concurrently means that you’ll both be returning to work when the baby is 6 months old, rather than a year old (I’ll deal with our approach to that later), it does have several advantages:

- Being there at the same time meant things were easier for both of us – an extra pair of hands makes many things take less than half the time, and be more than twice as easy. You can go to the toilet on your own, you can make a sandwich, etc. Seriously, it is hard to overstate how big of a deal this is.

- Not only is the essential stuff easier, but you’re able to do much more and be much less stressed and exhausted. I’ll dig into two examples of this below, being travel and sleep.

- There is no worry for the mother regarding the father’s imminent return to work, leaving her alone to cope. In the UK, fathers tend to get the first 2 weeks off, which allows them to help in the very early days, but many people understandably find it very difficult when this 2 weeks is over.

- This approach greatly facilitates equality by making it easy to ensure that mother and father are taking an equal role. There is no period in which the mother is the sole caregiver, learning the ropes on her own, so the father can participate equally in all aspects of looking after the baby, and contribute to a shared understanding of what works and doesn’t work for the baby.

- It also means that both parents are taking an equal hit to their respective careers, so neither is sacrificing more than the other in terms of long term prospects.

- As both parents are equally present, the child isn’t disproportionately clingy with one parent over the other. They can usually go to either parent when there’s a problem or they’re upset. They might still have occasional mum days and dad days (and to be fair, for us there were more mum days than dad days), but not exclusively one or the other.

- The baby doesn’t get used to one parent always being around, which often makes an eventual change-over to the other parent at 6 months very difficult.

- The mother isn’t in the position of dealing with the difficult first few months, while the father takes over and gets the “victory lap” of 6-12 months, where the baby starts to crawl, might say first words and take first steps.

- It may possibly aid language acquisition, as there are always 2 people around talking to each other, rather than a single person with no-one to talk to unless they brave going out.

- In the UK, taking less than or equal to 26 weeks off means your employer is not legally permitted to make changes to your job. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they won’t, but it gives you both recourse to challenge any changing of responsibilities that they might try to force upon you.

For ourselves, this was a wonderful bonding time for all of us. It brought my partner and I even closer together as we supported each other on a very intense new learning experience. We were able to work together as a team to overcome obstacles, share the burdens and the joys, and be far more adventurous than we would ever have been on our own.

Sleeping in Shifts

Sleep is a controversial topic, as everyone thinks they have “the solution” for getting babies to sleep, but inevitably all babies are different, so people’s advice may not actually be very helpful. Thankfully though, I’m not actually going to talk much about the baby’s sleep – it’s the approach to our own sleep that was unusual and successful here.

Newborn babies don’t sleep through the night and need feeding every couple of hours, which means that anyone looking after a baby on their own will necessarily be sleep deprived for weeks on end. Because we were both around for the first 6 months, we were able to deal with this in shifts. In this situation, if you’re bottle feeding, it is fairly straightforward to take it in turns to feed a baby. We opted to breastfeed, which made things a little more complicated, but ultimately we used a bottle for one feed overnight (more on this below).

By using a bottle overnight from 2 weeks old, I was able to take the baby for a 4 hour stretch, allowing my partner at least 4 hours of uninterrupted sleep (between a last feed around midnight, and a first feed around 4am, with a bottle feed from me halfway in between). As the baby started sleeping longer, this was able to be stretched out such that before 1 month old, my partner was able to sleep a solid 8 hours a night (between a last feed at around 10pm and a first feed at around 6am, with me giving a bottle at 2am).

This shift-based pattern, with my partner going to bed some time between 10pm and midnight, and me going to bed between 2am and 4am worked incredibly well, and meant that both of us could operate with minimal sleep deprivation well before the end of the first month. This is a dramatic contrast to several people that we have talked to, where the mother had not had an unbroken 8 hours of sleep for 2 months straight. The avoidance of sleep deprivation ultimately meant that this period was much less stressful than it could have been, and it was much easier for us to support each other.

In fact, this pattern was relatively easy to flex as the baby grew older. As they started sleeping in longer chunks, they would wake later in the morning and we could move the bottle feed gradually earlier. By 2.5 months old, we had moved the bottle feed to before midnight, and the baby would regularly sleep through until after 8am. Your mileage may vary greatly here, and I think that we were exceedingly lucky to have a baby that slept so well, but our approach meant that if they hadn’t been such a good sleeper, we would have been able to get enough sleep regardless.

The shift pattern also meant that I could stay with the baby while my partner slept, so that the baby wasn’t alone if and when it woke up. This is something that we had read was recommended in Philippa Perry’s “The Book You Wish Your Parents Had Read”. I therefore wasn’t desperate for the baby to go to sleep, so that I could go to bed too; as I wasn’t particularly tired, with my sleep cycle shifted by about 5 hours. This made for a relaxed night-time routine, which was very helpful, as being stressed about bedtime is a surefire way to ensure that the baby won’t sleep.

Combi feeding

In general, from what I can tell, most people tend to go down the “exclusively breast-fed” or the “exclusively bottle-fed with formula” route. I’m sure there are some people that do both, but a lot of the advice we read seemed to warn of things like “nipple confusion” or suggest that you only try introducing a bottle after 3 months. This no doubt puts some people off, such that they don’t try it.

We couldn’t find any good evidence that “nipple confusion” was a real thing – only occasional anecdotes, and scare stories from dogmatic “breast is best” advocates. The 3 months suggestion seemed to stem from the concept that feeding becomes a conscious action somewhere around that time, which can lead to things like bottle refusal around this time. This was a useful thing to be warned of, but didn’t seem like a good reason not to try it.

The main concern that we could see around doing both, was that using formula milk for some feeds means that you are not stimulating your breast milk supply. Depending on how many feeds were breast vs. formula, it is conceivable that this could cause issues. With that in mind, we opted to use pumped milk for bottle feeds, which meant that the baby was technically still exclusively breastfed (but hey – to each their own – I am passing no judgement on people that use formula).

I started giving the baby 1 bottle of pumped milk each night when they were 2 weeks old, which as mentioned above, guaranteed my partner at least 4 hours of uninterrupted sleep. As the baby slept longer and this became less necessary, we shifted to a double evening feed to tank the baby up overnight and enable them to sleep even longer before waking hungry.

We found that milk supply was higher in the morning, so pumping in the morning and using this at night was very helpful. It was possibly also beneficial for sleeping, due to “overnight” hormones in morning milk.

We had heard that it is worth having a variety of bottles and teats, as babies can be choosy about them and refuse certain bottle styles. We did indeed find that our baby was very picky, to the point where the only thing that they would reliably drink from was a Munchkin cup as pictured. This meant they were actually drinking from a “cup” from 10 weeks old. You go with whatever works!

Baby Carrying

This one is definitely not going to work for everyone, but we decided to exclusively use a baby carrier/papoose rather than a pram/pushchair. In fact, we still don’t own a pram! Our initial reasoning was fairly straightforward – firstly, we live in a large city with lots of steps near our house and even more steps to access public transport, making the idea of continually hefting one up and down all these steps unappealing. Secondly, we didn’t really have much space in our house to store another huge item of what is effectively furniture. Thirdly, prams all seem to be ridiculously expensive – we thought we would try it without one, to see if we really needed it.

There are certainly a few disadvantages to not using a pram – it is more physical effort to use a baby carrier, and you have less storage with you, so we often had to take a rucksack with us. That being said, the initial reasoning that we used turned out to be pretty sound – baby carriers are much smaller and easier to store, and it was pretty easy going out and about without having to manoeuvre a pram through a bustling city. Squeezing into cafés and shops was not a problem either, and it was great not having to worry about where to park a pram every time we attended a playgroup. We also both got stronger as the baby grew, so the physical effort wasn’t actually that bad.

What we did find though, was that there was another huge advantage that we hadn’t even considered initially. As the baby is much closer to adult eye-level, they get much more interaction and eye contact with other people as you walk around. This naturally made it much more likely that people would talk to them, helping with sociability and possibly improving language acquisition. It is hard for me to overstate how stark the difference was in this sense between being carried and being in a pram. In a pram, down at hip-level, a child doesn’t spend a lot of time looking up at the faces of people around, and only the most exuberant of people will stop to wave at a child in a pram. In a carrier on the other hand, we found that our baby was constantly looking at or smiling at (and sometimes shouting at) people passing by, and a majority of these people would at the very least smile back.

From about 6 months old, we started doing shoulder rides too, which was less tiring (the weight pushes directly down onto shoulders rather than pulling you forwards or back). Shoulder rides are a bit more limiting, as you don’t have both hands free, but on the other hand, it is much quicker to pick up and put down the baby without a carrier. Our child, being a bit of a daredevil, really loved this, and still quite likes this mode of transportation age 2.

The closest thing to a pram that we have now, is a sit-on scooter that we can push along, but this is so much tinier and more lightweight than even the most minimal pushchair. It also requires more effort from the child – rather than simply sitting and relaxing, they have to engage their core and stay on, as well as giving them the opportunity to learn to steer. This additional effort means that our energy levels aren’t completely mismatched – after a long day of walking around, we don’t have a hyped up toddler that has been sitting around all day, so we all get to have a bit of a relaxing evening.

Taking a Long Holiday with the New Baby

This is the one that comes up the most in conversation, and that people have consistently thought that we were absolutely insane for doing. We flew to Mexico for 6 weeks with our 4 month old baby, and did a road trip from Cancún to Mexico City and back. Personally, I can’t recommend it enough – after all, without taking a sabbatical, when else are you going to have the opportunity to go on an extended holiday like that. Obviously, this only works if you’re both taking parental leave concurrently, but it is another great reason to do so.

We did build up to it of course – when the baby was born we visited family and worked our way up to longer car trips. We then tried flying by taking a weekend trip to Bucharest. Once we were comfortable with all of that though, it seemed pretty manageable. The trip was a really great time, allowing the three of us to bond. It also wasn’t particularly disruptive to our way of living, as at that point there was no existing rhythm to break out of – everything was still new to us anyway.

Travelling around a new country, we found that all of the walking involved helped us to stay fit without really thinking about it, though this may just be our approach to holidaying – I’m sure it would be possible to do less walking than we did! People were also generally very kind and pleased to help with and interact with the baby.

Fundamentally, we enjoy travelling, and didn’t want to stop just because we were now parents. That being said, we did change our approach to make it enjoyable for the baby too – we avoided driving for too long on any one day, and we made sure to facilitate naps and snacks as required. By now, we have travelled quite a bit with our baby, and despite a few people suggesting that they wouldn’t get much out of the experience, the reality appears to be quite the opposite. We have generally found that significant developmental spurts seem to coincide with holidays that we take as a family.

Sign Language

Hand signs are much easier than words for a baby to coordinate and formulate. This shouldn’t be too surprising, as even adults often find mimicking a new sound to be quite challenging, but mimicking a hand movement is much more straightforward.

Babies can understand things that are said to them far earlier than they learn to speak, so by coupling certain words with hand signs, the baby is able to associate the concept with the sign as well as the vocalisation. This allows them to attempt to communicate much earlier, and when they can communicate even a rudimentary thought, this is very empowering.

We’re not proficient signers, so we weren’t anywhere close to saying everything both verbally and in sign language – we just used a few key signs that allowed for the most common concepts to be signposted. These signs were: More, All Done, Food, Water, Milk, Potty, Yes, No, Mum, Dad, and Nappy Change.

For us, their first sign “potty” happened just before 5 months old, “more” at 6 months, “milk” around 8 months, with “food” and “water” at 11 months.

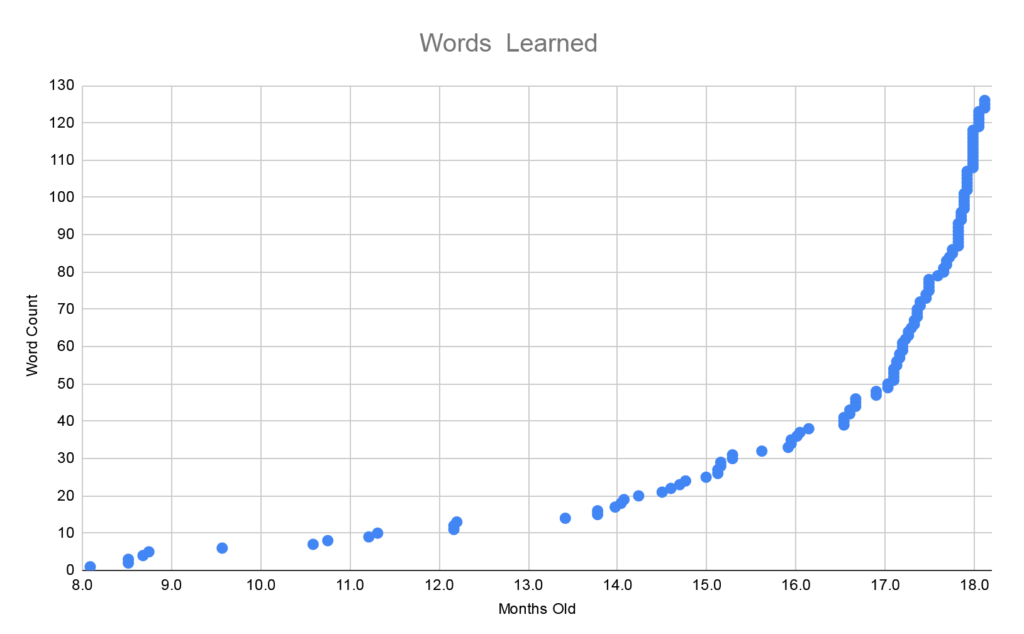

In contrast, their first word was at just over 8 months (“dad”). Learning and using these few signs didn’t actually take a lot of effort, so I would say that it was worth it. Only just though – largely because they took to speaking so quickly: first word at 8 months, 10 words by 12 months, 100 words by 18 months. If they had taken longer to become verbal, the sign language would have been useful for longer.

On the other hand, I can’t rule out the idea that sign language could have itself aided wider language acquisition. It would be very interesting to see a study on whether using basic signs with babies accelerates their use of verbal language.

As a side note, the other things that we did that we have reason to believe had a positive impact on language acquisition are:

- No dummy/pacifier – this seems to be a standard recommendation by doctors, so we decided to just never get one.

- No baby talk – we talk to them normally, without using cutesy child-specific words (like “horsey” and “din-dins”), which made recognition of words used in conversations between adults more easy.

- As mentioned above, both parents off at the same time meant conversations constantly happened around them.

- Similarly, baby carrying meant they were at adult eye level, so conversations when out and about didn’t go (literally) over their head.

- The holidays were a break from normal routine, so different conversations and words were used.

- We’ve made great use of the Usborne “first thousand words” book, which quickly became a favourite, especially the “opposites” page.

As you can see from the above graph, word acquisition tracked pretty close to exponential. While we stopped tracking individual words at about 18 months, because they were coming too rapidly to keep track, this trend has continued.

It took about 6 months to go from 10 words to 100 words, and after another 6 months, by age 2 they knew all the words in the “first thousand words” book, so definitely had well over 1000. At 2 years and 3 months they had picked up words like “consequences”, “frustrated” and “antibiotics”, and my favourite sentence so far is “want to go on rocket to moon on adventure holiday”.

I say all of this not to brag (well ok, maybe a little – I am very proud of them), but to make the point that some of what we’ve done must have had an effect. I’m not one for false modesty, so I’m comfortable saying that my partner and I are reasonably intelligent, but neither of us is John Von Neumann or Giuseppe Mezzofanti. We therefore have no reason to expect that our child has superhuman language abilities. The generally expected rate of language acquisition seems to be first word between 10 and 14 months, 100 words by age 2 and 1000 words by 3. It seems likely to me that some of the approaches that we have taken will have contributed to roughly halving this doubling time.

Elimination Communication

This is an approach to nappies and potty training that focuses on giving babies an awareness of their bodily functions and the ability to communicate about them as early as possible. Usually focused around noticing trends and cues from your baby, to allow you to put them on a (tiny) potty before they go in their nappy, and avoid them getting used to soiling themselves. Many proponents of the various techniques claim that their babies have been “potty trained” at stupendously early ages. This is probably best taken with a pinch of salt, but I can share our experience.

The concept of Elimination Communication is nothing new (hence there being an established name for it), however it definitely seems to be less prevalent in the UK than it is in the US, as most of the resources we came across were from the States. Without wanting to stereotype anyone, it also seems that a large number of people currently practising and espousing this approach are quite far towards the “crunchy” end of the spectrum (by which I mean the lifestyle that is often typified by a kind of hippie organic vegan asceticism). This is a little unfortunate really, as I don’t think there is any need for it to be associated with this, and the perceived association might put off people that have more conventional lifestyles.

We came across the general idea independently some time ago. My partner spent some time living in China around a decade ago, while western brands and products were still trying to make inroads into their markets. During this time, she encountered many families with quite young babies that did not use nappies at all, and seemed to be able to sense when their babies were about to go. When out and about, these parents held their babies over bins, drains or bags to do their business, and seemed to have a remarkable amount of success.

It is my understanding that unfortunately these days most people in China look down on these practices, and tend to use disposable nappies as much as people in Europe and the US. At the same time, in the UK at least, the average age of potty training completion has gone up from 2 ½ to 3 ½ in just the last 20 years, and 24% of children start school without being potty trained. The average baby also gets through around 10,000 disposable nappies, which are all either burned or get sent to landfill. After some research, and discovering that the idea of “Elimination Communication” seemed to be attempting to explain and codify a similar approach among parents in the US, we decided to give it a go. Obviously, we’re not out there letting our baby defecate into bins, but we did invest in a number of tiny travel potties, and are intimately acquainted with the locations of public toilets in a large number of destinations…

The approach requires far more detail than I can include in this post, but we found that the most useful resource was “The Diaper Free Baby” by Christine Gross-Loh. We didn’t worry too much about some of the suggested actions such as overnight pottying or “naked observations”. We mostly just offered our baby the opportunity to use a potty at nappy changes and transitions between activities (sleeping and waking, feeding and playing, etc.). Prompting the baby with cues when on the potty was also helpful for us (using a hand sign and grunting).

The other thing that we did, which seemed to help, was to use reusable nappies. They are less absorbent, so the baby lets you know that it is dirty earlier. This may sound unpleasant for the baby (after all, most nappy marketing focuses on how comfortable they will feel, despite having thoroughly wet/soiled themselves), but it avoids them getting too comfortable with soiling themselves, which is then something you have to train them out of doing later. It results in you needing to change the nappy more often, so that the baby doesn’t get uncomfortable, but we were happy with that trade-off. Mind you, we still used disposable nappies on holiday – they’re much more convenient, you can buy them at your destination, and you don’t need to wash or carry around a bunch of dirty nappies. All in all, I think what we did roughly amounts to what some refer to as “Lazy EC”, but we found it to be immensely beneficial.

“Babies used to be potty-trained much earlier, and more willingly, because towelling nappies were so damp and uncomfortable. But the moisture-wicking technology of the disposable has made it possible for toddlers to sit for hours quite happily in their own feculence.”

The Telegraph, as ever, raging about the issue in much more hyperbolic terms

By providing the baby with a hand movement and a noise that was associated with going to the potty, the baby was empowered to be able to communicate their needs. Our baby was able to signal to us by grunting that they were about to defecate by 4 months old. This meant that we were usually able to get them onto the potty in time, which was actually a source of considerable happiness for our baby. When you are that small and powerless, it must be reassuring to be able to control even a tiny amount of your world. Despite requiring an initial investment of time and effort, it paid dividends much quicker than we had hoped, such that by 6 months old, we were hardly dealing with any dirty nappies – only wet ones, which was great when the baby had started weaning. By this point, we also tended to read books on the potty to make the potty experience more enjoyable.

We started potty training at 19 months old, going cold-turkey using the “oh crap method”, and were able to do away with nappies entirely at 20 months old, even during naptime.

We still used reusable pull-ups overnight for a few more months, but these were only for the occasional accident that happened less than once per week. We might have been able to complete potty training earlier, but there wasn’t much urgency, as we were only really dealing with the occasional wet nappy at that point.

Baby Led Weaning

There are a range of different approaches that could all be described with this label, and as with many things, the most extreme versions can create their own set of problems. Despite liking the general philosophy of consent based parenting, the main issue that we had with “gentle parenting” and “child led” approaches is that many people seem to take them to extremes.

There are many skills and behaviours that children need to learn in order to be functional people. In our view, it is not good enough to just sit back and wait for them to express interest – you have to generate the interest yourself! Getting a child to do something when they aren’t interested is often difficult and counterproductive, putting them off even more, therefore it is important to make the activity fun and appealing.

We were planning to start weaning at about 6 months old, but our baby ended up being very interested in food, and started grabbing and tasting things that were on our plates at just over 4 months. They didn’t really start ingesting significant quantities until around 6 months, but by this point their dexterity had improved dramatically.

The main tenets of “baby led weaning” that we embraced were:

- They eat the same thing as you – no need to prepare food separately, you just have to avoid too much salt and preferentially chop things into stick shapes that they can get their fist around. They therefore get used to eating as much variety as you do.

- They eat at the same time as you, at the dinner table – they don’t feel like they’re being watched over while they eat, they can just copy what the adults are doing.

- It doesn’t matter how much they eat – it’s about the experience and the enjoyment.

This made life easy – no blending everything into a mush, no cooking two separate meals every mealtime, very little spoon feeding. I think that we were very lucky to have a child that was keen on food, but I don’t think we’d have changed much if they weren’t.

We weren’t too obsessive about avoiding sugar, for example our baby ate quite a lot of fruit, but we tried to steer clear of desserts until age 1, and only occasional small portions thereafter. This had the unexpected benefit of making them take Calpol very easily. A couple of different doctors have made the comment that “they take medicine well – they must not eat much sweet stuff”.

We also weren’t that extreme about things being “baby led” – if they didn’t want to eat something, that was fine, but we still kept offering it at mealtimes, and gently encouraged them to at least try it. Often we would find that a few weeks after trying and disliking something, they would suddenly start eating it for no discernible reason.

Having a Flexible (and Late) Routine

Most parents we encountered had quite rigid schedules for sleeping, naps and eating, and many set quite early bedtimes despite not enjoying the very early mornings. We wondered why this was, as the rigidity was often quite limiting and felt unnecessary; while the early mornings sounded unpleasant and seemed easily resolved by a later bedtime, despite people clearly not taking this option.

Several people we spoke to considered this rigidity to be the only way that worked, but we decided to see whether we could avoid these limitations, and we found that we could. It was a lot more pleasant – naps/food were not “expected” at certain specific times, so we could fit them in more easily around other activities that we did during the day. This also made it easy to adapt to changing requirements (e.g. 2 naps down to 1 nap wasn’t a huge adjustment – two 2hr naps became two 1.5h naps, which then became one 2.5h nap etc.).

Due to eating dinner at the same time as us, our baby generally had a bedtime of between 21:00 and 21:30. This caused us no issues, and by 6-7 months old, it resulted in a usual waking time of 8:30 – 9:00. Many people would consider this a very late bedtime, but the baby was getting the same number of hours of sleep as other babies their age – it just meant that we didn’t get woken up at 6am every day, which was glorious.

Once we were no longer both on parental leave, this late bedtime had another huge advantage. Arriving home from work after your child has already gone to bed, whilst regrettable, is a pretty normal experience for many people. Due to the later schedule, in the almost two years since we returned to work, I think this scenario has only happened once or twice to each of us.

One justification that we heard for not having such a late bedtime was that “they’ll just wake up early anyway, and then be grouchy all day”. This didn’t gel with our experience of travelling, after all, if you’re waking up at the same time each day, and that isn’t the time you want to wake up, that is just jet-lag. As with many adults, the process of overcoming jet-lag can take a couple of days, but after a couple of days of broken sleep, you all settle into a new routine.

When travelling, skipping a nap was a good way to bring bedtime forward by a couple of hours, and a later, longer nap was a good way to push bedtime back by a couple of hours. If our baby woke up in the middle of the night, they were generally still pretty tired, so comforting them back to bed would usually take less than half an hour. The same techniques we used to help our baby overcome jet-lag were useful in ensuring that their sleep cycle was properly aligned with the 21:30-8:30 sleep window.

Floor Bed

We encountered this idea through researching Montessori methods, which in general seemed quite well aligned with how we wanted to approach things (e.g. treating the child as an independent person, and being mindful of their desires and opinions – Philippa Perry’s book was very helpful for this too). We definitely haven’t been following Montessori methods to the letter, as they can be quite prescriptive, but we used it as inspiration, and Simone Davies’ books “The Montessori Baby” and “The Montessori Toddler” were very helpful for this. It also has some clashes with other approaches that we were using, which I will briefly detail.

In conflict with EC, the Montessori approach says that you shouldn’t disturb playtime, as play is work, whereas EC suggests that you offer potty as soon as you see a cue. We tended to interrupt play if they deliberately cued or were distressed, but were more relaxed about more subtle, non-deliberate signals. With offering the potty at transitions between activities, we found that they developed the ability to hold it in until they were next offered the potty (within reason).

In conflict with BLW, the Montessori approach suggests having babies at their own tiny table, whereas BLW tends to have them at the same table as adults, able to watch adults eat, and eat the same things as the adults. We tended more towards BLW, as eating with us was more convenient and encouraged interest in more adventurous foods.

Interestingly, the idea of a floor bed seems to be one of the less popular Montessori concepts, possibly because of how unusual it appears at first glance. Child-proofing an entire room, and setting it up for them to have free reign within it, does make it look very different to what you might expect from a traditional baby’s bedroom!

We moved them from a bedside cot to their own room with a floor bed at about 6 months old. In the early days of this, we would tend to go in whenever they stirred, so that they wouldn’t feel abandoned, but we found that they very quickly adapted to the change, and quite liked the independence. A video monitor was invaluable, as this enabled us to keep an eye on what they were doing. Rather than needing our help to be let out of a crib, they were free to explore, and this led to them being much less likely to cry when they woke up in the morning. It also meant that we didn’t have to lift them out of their cot, which meant much less strain on our backs as they grew heavier.

When we first moved them to the floor bed, we found that they would often roll out, so we used some lengths of pipe insulation (similar to a pool noodle, but much cheaper and narrower), under the bed sheet, creating a slight barrier to avoid accidental rolling. A few times we found that they had gotten out of bed in the middle of the night, and were asleep elsewhere in the room, but this wasn’t really a problem – we could usually go in and gently move them back into bed. After a couple of months, they started to crawl, and they started heading back to bed themselves when they awoke in the middle of the night (sometimes falling asleep before they made their way all the way onto the mattress). At this point we removed the roll barriers, so that they could get back into bed more easily.

From quite early on, our child would often wake up and play independently for up to 20 minutes before getting bored and demanding our presence. This was great for gentle starts in the morning. Not feeling trapped in a crib also made them much more inclined to go to bed. I can imagine that if you were to dislike your bed, you would be less likely to volunteer to go there, but by 11 months old, our baby would sometimes take themselves to bed if they were tired enough!

One further benefit was that the floor bed helped them to get used to there being a drop at the edge of the bed. After we removed the roll barriers, they initially rolled out of bed at some point on most nights (though this didn’t usually wake them). This quite quickly became more of a rarity though, and by age 2 we were comfortable putting them in a standard bed, raised off the floor.

Both Parents Working Part-Time

Aside from taking parental leave together, this has had the biggest impact on how we live our lives, and I am very happy to strongly recommend it to anyone that will listen. Both my partner and I used to work 5 days a week, as is the norm, but on returning from our 6 months of shared parental leave, we both went down to 3 days a week. After all, 6 months old is very early to go into full-time childcare, and neither of us wanted to stop work completely. Thankfully in the UK, companies have to have a “good business reason” to deny such requests, so we were able to clear this with our respective employers before the baby was born.

My partner works Monday to Wednesday, and I work Wednesday to Friday, which means that every week we each have 2 days looking after the baby by ourselves, with weekends together as a family, and only one day on which we need to pay for childcare. With only 1 day per week at a childminder, it isn’t too expensive, so we don’t feel like we are working just to pay someone else to raise our child, as people often feel when both parents stay in full time work. Although we currently live a bit far from our respective families for it to be relevant, 1 day per week is a small enough amount that some people might even be able to find family or friends that can help, without it being an unreasonable ask.

From an egalitarian perspective, this approach works incredibly well when contrasted against the model of one working parent and one stay-at-home parent. We both share the responsibility for child rearing, being able to appreciate the difficulties of both childcare and work. This allows us to share different approaches with each other, and support each other, as we are not living in totally separate worlds. In a more traditional situation, with a stay-at-home parent, it is very easy for the parent in employment to generate frustration by simply offering their opinion, or trying to help. After all, it is difficult for this to not come across as “I know better than you, despite having hardly any experience”. As equal caregivers, suggesting alternative approaches to each other is much less likely to generate frustration, and those suggestions are much more likely to be actually useful.

Among other things, most relationships are built on a foundation of shared experiences, which may be why many couples find that the first years of raising a child takes a significant toll on their relationships. If one of you opts to be a stay-at-home parent, you will start to have very different life experiences from each other. Further to this, if you aren’t the one doing a job, it is very easy to fail to appreciate how much hard work it can be. By both getting the experience of looking after our child, we are able to share in the experience and bond over it, as well as being able to appreciate the difficulties that the other is having.

By spending 3 days out of each week at work, we are both also able to maintain our respective careers. We both get to interact with other adults regularly, avoiding the stay-at-home pitfall of chronic loneliness and ego death. Neither of us will have a gap on our CV or in our professional development, and whilst we might find that our progression slows down relative to full time workers, we are both sharing that hit as equally as we can. Further to this, neither of us is the default “primary caregiver” – both of us are the caregiver on our respective days. Some employers have an issue with parents that are part-time workers, because they often have to leave early when their child is sick, but this isn’t the case here, as on work days, the other parent is the caregiver.

I have heard from several people that (for various reasons) work part-time at 4 days per week, that the 4-day week is quite problematic. Employers tend to expect the same amount of work from you as if they were paying you for 5 days, and by working late, this is actually possible to deliver. As such, it can be difficult to enforce a boundary with the employer, that you should in fact be given less work, and not have to work late to compensate. A 3-day week does not have this problem – with the best will in the world, a full time job cannot be crammed into that timeframe, so employers have to adapt their working procedures around it. Of course, they may use this as a reason to deny the part-time request, or just make your life difficult, but more and more employers are coming to terms with part-time working, so it’s probably worth a try.

For weaning and sleeping specifically, there were distinct positives to the father having regular 1-on-1 time with the baby. Having breastfed the baby, weaning was much easier on the days mum wasn’t around, as the baby has less expectation of being breastfed. Similarly for sleeping, in some circumstances it was easier for dad to settle the baby, as there was no expectation of being fed to sleep.

Aside from the egalitarian angle, there are a few other advantages that we have found to this approach. For families in which both parents return to work, separation anxiety can be an issue, and some babies start waking in the night as a result. By avoiding full-time childcare, we didn’t have to deal with this – our baby adapted to 1 day per week at a childminder in hardly any time at all, as they very quickly realised that it was only for a single day at once. The multiple different approaches used between dad, mum and the childminder were also very useful in reducing blind spots. We were all much less likely to miss something, as we all had different thought processes and experience.

No Screen Time

One thing that we were quite vigilant about was avoiding screen time. This is another controversial topic, as I think it is something that many people feel judged about. I want to make clear that I am not passing judgement on anyone that gives their kid screen time – it is a personal decision, and it would have been much more difficult for us to stick to if we weren’t sharing the effort by working part-time.

While several studies have shown that “excessive” screen time can negatively impact executive functioning and sensorimotor development with long term effects, it isn’t always clear what counts as excessive. We did however come across various anecdotes suggesting that any kind of regular screen time has some negative impact, and some people have found that weaning their children off screen time helped them to sleep better and develop better self-regulation and patience. As such, we made significant efforts to avoid screen time, and used it only as a last resort a couple of times, watching one or two episodes of something when 1) we were on a long-haul flight and 2) we all had COVID and could barely function.

One thing that seems very clearly inversely related to the amount of screen time they get is a child’s ability to play independently. By avoiding the promise of instant gratification that a screen provides, we found encouraging independent play much easier. Ultimately, a child without access to a screen needs to learn how to entertain themselves. To encourage independent play, we tried to leave them to it some of the time – finding things that would entertain them, and then leaving them to play with the toys by themselves. Another quite Montessori approach.

Whilst this may have made life a bit more difficult in the early days, for us it definitely paid off in the long run. Having learned to play independently, and not being used to screens being on offer, they generally don’t make demands to watch anything. They are also able to sit in restaurants and be entertained by the food, a toy or other people, without needing a screen.

Books and Letters

We have tried hard to make words and numbers interesting and exciting. As mentioned above, it’s difficult and counterproductive to get a child to do something they’re not interested in. Therefore we have read books to our baby from the start, and engaged with the content in a way that makes it exciting (“look, it’s a fish – blub blub”, etc.). This has engendered a love of books in our child, as intended, which is a good sign for future learning. There is nothing particularly new or controversial here, as reading to your child seems to be one of the only things that has been conclusively shown to improve educational outcomes in children in a statistically significant way.

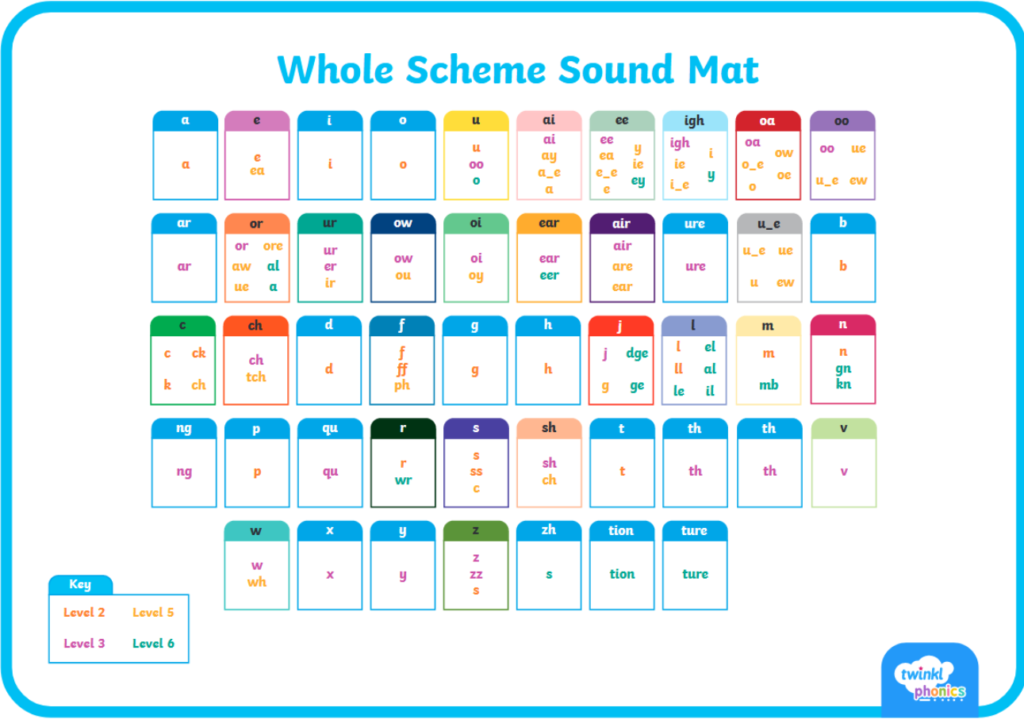

Having succeeded in generating an enthusiasm for books though, we have been able to take this one step further. We were given some letter/animal fridge magnets around age 1, which we mainly played with as an after dinner treat (since they were in the kitchen). Having looked into Phonics a bit, we tried to be consistent in our use of the letter sounds for the letters (rather than using the letter names), and this turned out to be one of the best toys we had. It really sparked an interest in letters, and before long we had stuck up a few letters from a phonics chart in the kitchen too, which our baby loved pointing at and trying to make the sounds.

It is worth noting that all of this was driven by the enthusiasm and interest that they showed – we weren’t sitting there and forcing our 1 year old to pore over phonics charts. We just made the letter magnets seem exciting, and they started noticing letters when out and about as a consequence.

Shortly before age 2, they were able to recognise and sound out every letter of the alphabet. We looked into the next steps in phonics, which was not entirely trivial, as most resources either stop at this point, or are targeted at parents supporting the learning that is being undertaken at school. Thankfully a friend that was a teacher was able to point us in the right direction, and we were able to start on digraphs and dipthongs.

By their second birthday, we acquired a much bigger set of fridge magnet letters (made of smaller letters, without the animal associations). These probably wouldn’t have been of much interest before, but by this point, letters were interesting to our toddler in themselves. These immediately jumped to being one of the favourite toys (behind only the favourite teddy and perhaps the duplo chickens…). After only a couple of months of playing with them (“dad, spell edamame on fridge”), they’re able to recognise some 3 letter words like cat, mum, fix, etc.

Numbers have been similar – lots of reading number books, and counting objects. Our toddler is able to recognise all of the digits from 0 to 9 (still occasionally gets 6 and 9 mixed up, but gets it right more than half the time). I say this not to brag, but to assert that it is possible. The number of people I have encountered that thought that what we were doing was pointless is staggering. “Oh, they’re far too young to recognise numbers yet” – well yes, that was true at one point, but by seizing the opportunity to show them, every time they expressed an interest in a number book or a letter magnet, we were able to keep them interested enough to learn. The attitude of “they can’t do it yet, so don’t teach them” is one that I personally find quite bizarre – after all, how do you expect to teach something if a prerequisite to teaching the thing is them already knowing it.

What is more, this process is a lot of fun. There is something truly wonderful about showing someone something new for the first time, and watching it sink in. Every success is exhilarating; every time they recognise something and are able to apply it outside of the environment in which they learned it, is a rush of adrenaline. This is something that we are only able to do because of the way that we have set up our lives – part time working, which allows us to use minimal outside childcare, whilst also allowing us both to maintain our careers and not get burned out being a carer. This means that most weeks we come to our 1-on-1 days reinvigorated, with excitement, energy and new ideas.

As mentioned previously, I wasn’t expecting to enjoy the first few years of having a child at all, but I can honestly say that the way that we’re approaching it has been far easier and more fun than I would have dared to dream. If someone offered me 10x my salary to come back and work full time, I would have to respectfully decline – there is more to life than work.

“No one on his deathbed ever said, ‘I wish I had spent more time on my business.’”

Arnold Zack in a letter to Paul Tsongas

It’s a good job that we feel this way really, as our second was born just a few weeks ago. When I said “we will definitely be doing the same thing next time”, I really meant “we are doing this again, right now”. Time will tell whether our various approaches will be as successful a second time around, but so far I am reasonably confident that they are sufficiently flexible that we can make them work for another different child.

4 Replies to “Doing Things Differently – Adventures Raising the Next Generation”

Thanks for the write up! An inspiration to aspiring parents like myself. One tactical question – when you were speaking to your wife in front of your baby, would you concurrently use the basic hand signs to each other?

Thanks! Regarding your question – not really – we weren’t practiced enough to remember to do that in the middle of a conversation, but we tried to use them consistently every time we talked to the baby.

Baby talk actually accelerates language acquisition, including using those “cutesy” words:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cogs.12628

Thank you for the read! Useful approaches that I will take away and consider!