Capitalism as a Social Cause

Even many proponents of capitalism seem to view investments as fundamentally selfish. They just view selfishness itself as a good thing, channelling the fictional Gordon Gecko’s mantra of “Greed is Good”. This is understandably unpalatable to many, and I think this perspective does capitalism a great disservice – twisting and misrepresenting the core concepts into something unrecognisable.

Here, I hope to reframe the discussion, explaining why the underlying concepts of capitalism and investment are good things in their own rights, and why those advocating for consumerism are actually wolves in sheep’s clothing. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves though – it might help to think about some of the basics first.

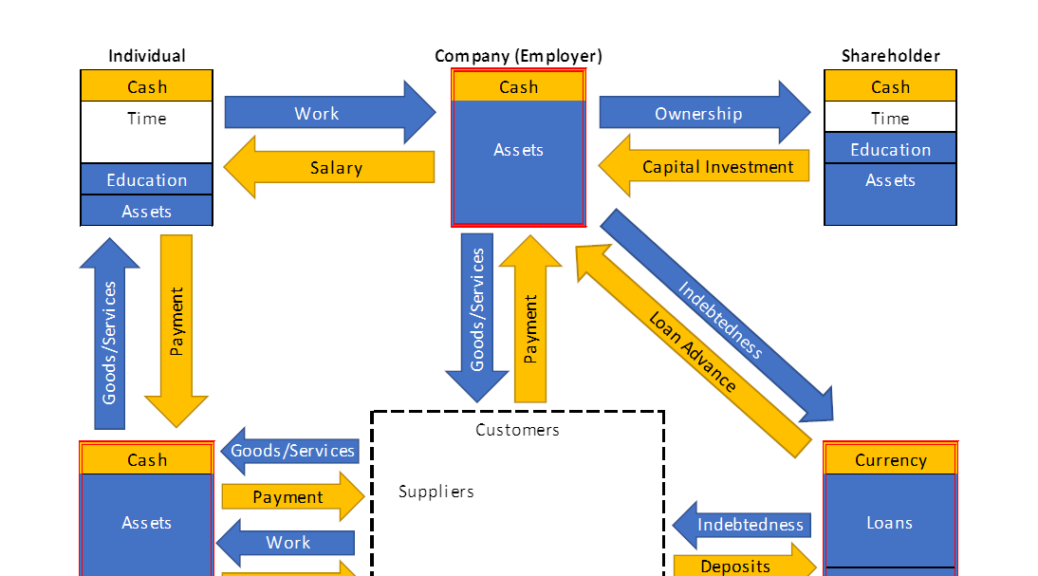

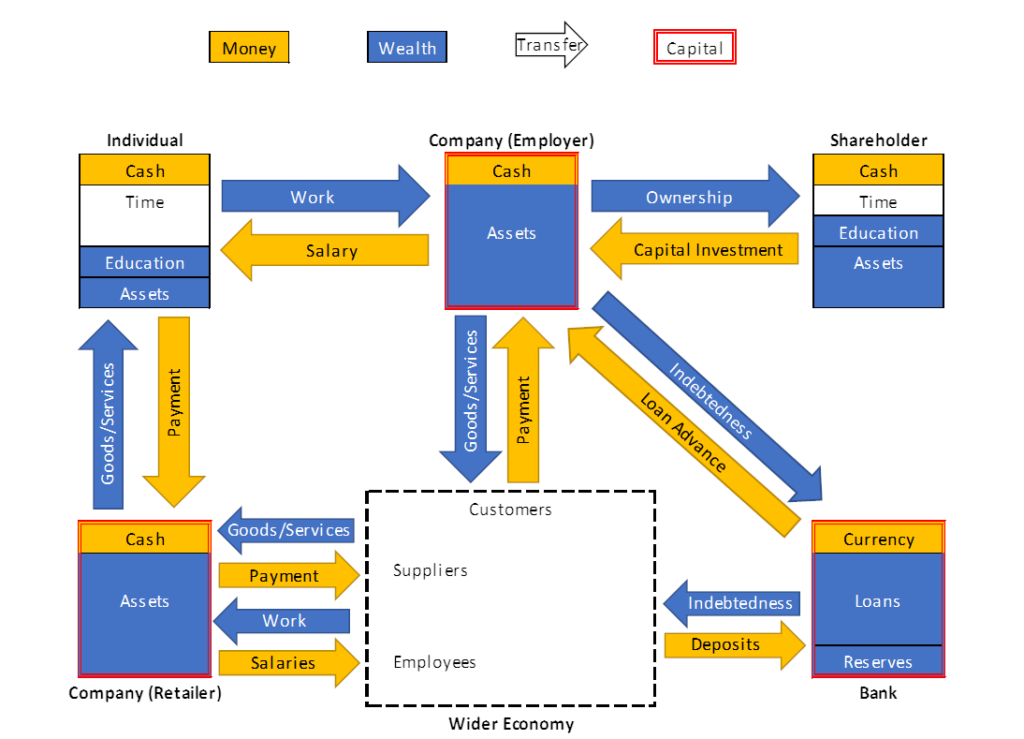

What do we mean by capital? From a finance perspective, capital is basically another word for money, but it is used in a specific way. From a business perspective, capital is usually associated with a cost – it is either equity or debt, both of which are lent to the company with the expectation of making a return. This is referred to as the “Cost of Capital”, and the returns that a company makes using the capital it has acquired is often known as ROCE (Return on Capital Employed). From an accounting perspective, this capital is therefore a liability – money that it owes, either to shareholders, or to creditors (like banks).

Companies then spend this money on machinery, inventory, overheads and employees in order to produce something of value to their customers. Everything a company owns, including its own profits are ultimately owed back to its shareholders and creditors. If a company makes a net profit, these “retained earnings” are also owned by and owed to the shareholders, so they increase the amount of capital present.

The flip-side of capital is the assets that this borrowed money was used to acquire. (Economists usually refer to these assets as capital goods or just capital, which they generally define as the “means of production”, though I am not going to use this definition here, as it would become confusing.) These assets could have been purchased directly, or have been produced by workers that were paid by the company. Ultimately, the capital present in a company is a monetary valuation of all of its assets (including any money it has sitting in its bank account).

So if capital is basically money that has been lent to a company, what actually is money? This might seem like a bit of a silly question, but it is worth asking. Now that we are no longer on the gold standard, money doesn’t have an intrinsic value like it once did. When we used the gold standard, we were really just operating a barter economy in which everything got converted into units of gold before being traded for something else. Money is clearly a measure of something that can be used to acquire goods and services, but what is it a measure of?

It is not a measure of “hard work” – many back-breaking jobs pay very little, while some other people do very little work, and accrue vast fortunes. It can however be viewed as a measure of the “net amount of beneficial contribution you have made to the wider world”. There are various ways for this metric to be subverted (worker exploitation, poorly negotiated contracts, taxes), which could have a big impact on individuals, but from a broad perspective, looking at the wider economy, this metric should be relatively reliable. The amount of money you get for something (an hour’s work, or selling an item) is determined by its market value – how much other people value it. Therefore the amount of money you have received should be roughly indicative of the amount of value you have contributed to the economy.

“Amount of beneficial contribution” is a bit of a mouthful, and is still not that well defined, so allow me to rephrase it. I am going to use the term “wealth” for this; it may sound like I am using an odd definition of the word wealth here, after all someone with a lot of money is generally considered “wealthy”. It is however helpful to separate these two concepts. What I mean here by wealth is effectively just all assets except for money (defining money in terms of money wouldn’t be very helpful).

An Asset is a resource controlled by the entity as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the entity

International Accounting Standards Board Framework

Importantly though, for these purposes I mean for wealth to include things such as a person’s education and experience that wouldn’t ordinarily be included by the formal definition of assets above. The control criterion means that employees and their expertise are not counted as assets – a company might pay their employees, but they do not control them in the strictest sense. An employee does control themself, so could consider their education to be their own asset, but this is usually just a colloquial use of a technical term.

At its core, wealth is the ability to either produce more assets or more happiness. This may just be a standard physical asset like a factory or some machinery, but can also be your own knowledge and experience. To attempt to avoid confusion, I am therefore using the term wealth, rather than using a non-standard definition of a technical term such as assets or capital.

By this definition, wealth is of course hard to measure, and its value is generally only really known at the point at which you sell your asset/your productive capacity/your time and expertise. If you own inventory of some product, or you own a factory that can produce that product, you could sell these for money; releasing it from your control, and contributing it to the wider economy. This amount of money is going to be roughly the amount of wealth you had before you sold it.

Likewise, if you sell your services either through employment or as a contractor, you are using your expertise to convert some of your time into wealth, for which you receive money (as you do not retain control of that wealth). If, instead of employment, you just make things (perhaps as an independent craftsperson/artist), you could still be creating wealth, but it is very difficult to value how much wealth you have created until you sell your wares.

I. The Wealth Must Flow

Even though wealth is hard to value, it is much less abstract than money. We usually view the economy through the lens of money, tracking its accumulation and its movements, as its easily quantifiable nature means that this approach yields very well to certain analytical methods. Ultimately however, this lens can make some things in economics quite counterintuitive. As an alternative approach, we could view the economy through the lens of wealth. We can easily witness the production of wealth by people investing their time and resources in creating things that people want. We can also see wealth being transferred around as goods change hands and factories change ownership.

Viewed this way, the flow of money around the economy is therefore a symbolic representation of the flow of wealth that goes in the opposite direction. Electric current is the flow of positive charge, while electrons are negative, so the actual “flow” of charged particles is usually in the opposite direction of the current. In just the same way, money flows in the opposite direction of wealth.

Of course, if you sell all of your assets, you no longer have them – you have the money instead. This money symbolises the amount of wealth you have released from your control, and gives you the right to purchase other wealth from the wider economy. That could be food, other inventory, a different factory, or shares in a company.

There is an important distinction here though – what would happen if you sold your assets, then put all of that money into a pile and set fire to it? Aside from this being illegal in many countries (though surprisingly not in the UK), you wouldn’t have consumed anything – the assets you sold would still exist. The only thing you would have done would be to exert a slight deflationary pressure on the currency – everyone else possessing units of that currency would be able to buy very slightly more with their money. It would have the same effect as if you had taken all of the money and transferred a bit of it to everyone else in the world in proportion to how much of that currency they possessed at the time.

On the other hand, what would happen if you had destroyed your assets? Well, obviously, they would no longer exist. This would be a shame – someone else could have used them, and now if anyone wants them they will have to be made again, using someone’s time that could have been used producing something else. The idea that destroying things helps the economy as you can pay someone to recreate them is a classic example of the “broken window fallacy”.

II. Creating and Destroying

Viewing wealth in this way is very helpful to make sense of a few things. Whilst money circulates in the economy in the opposite direction to the movement of wealth, it is only useful when it is being transferred around. You could almost take the view that money that is sat still ceases to exist – just as setting fire to a pile of cash “reduces the supply of money”, making the remaining money worth slightly more, even just stuffing it into your mattress would have a similar (albeit more temporary) effect. If cash is taken “out of circulation”, the supply of money in the economy is reduced.

If you put your money into a bank account, there is a slightly different effect. There is a common misconception that cash deposits in banks generate additional lending – that the additional cash allows banks to lend more money out. It is true that there is a direct relationship between the two, but it is actually the opposite way around – additional lending creates more cash. Don’t take my word for this though – the Bank of England has a great summary of how fiat currency works.

In much the same way that banks “create money” by advancing loans, repaying a loan “destroys money”. Just like matter annihilating with antimatter, it cancels out the debt that the bank holds (though thankfully, without the exciting explosion). As before though, this is not a problem, as destroying money isn’t the same as destroying wealth.

Even if you aren’t directly repaying a loan, just depositing your money into a bank account has a knock-on effect that results in the bank seeking to acquire more debt to offset your deposit. Your deposit could be viewed as reducing the money supply, but unlike stuffing cash under your mattress, it also simultaneously increases the bank’s demand for debt, which is equivalent to a decrease in the demand for money (debt is just negative money after all).

This means that unlike stuffing it under your mattress, putting money in the bank is not deflationary. (N.B. This is one way of describing this process – there are several others. Much like quantum mechanics, there are many different “interpretations”, but they all result in the same calculations and the same outcomes. I am also glossing over several details, so I recommend reading the BoE paper linked above.)

This also partly helps to explain “Quantitative Easing” – the government “printing money” also doesn’t create wealth – it just increases the amount of cash floating around that can be used to purchase things. By increasing the amount of cash without a corresponding increase in the amount of debt, it increases the money supply and therefore exerts an inflationary pressure, which has the effect of reducing the value of any cash that people have sat in bank accounts (or mattresses).

This can have a very powerful effect – the economy isn’t static, so whilst the amount of wealth is important, the flow of money also does have a critical role to play. (N.B. This is a slightly different mechanism to the monetary policy of changing interest rates to influence inflation. Low interest rates increase the demand for loans, and decrease the demand for cash. It is this decrease in demand for cash that exerts an inflationary pressure, rather than an increase in supply.)

Many businesses rely on a steady influx of cash, and cannot survive for long if this is disrupted (as we have seen during the recent pandemic related economic crisis). This is usually due to staffing costs and loans – layoffs are unpopular and re-recruitment is costly, whilst loans cannot be avoided without declaring bankruptcy or liquidating assets to repay them. Therefore if the flow of money around the economy slows down companies with high leverage or many staff will be the first to downsize or fail. Again though, QE is a policy that simply aims to increase the speed at which money changes hands – it doesn’t create wealth out of nothing, as using these definitions money is not wealth.

III. Explaining Stagflation

One example of a counterintuitive economic concept that becomes very clear when viewed from this perspective is stagflation – inflation that occurs despite slow growth and high unemployment. This is something that was considered physically impossible by economists, right up until it happened in the 1970s.

If you look at the supply of money relative to the amount of wealth, inflation occurs when the ratio of money to wealth increases, whilst deflation occurs when this ratio decreases. These can however both happen in two different ways.

If you print money, this generally increases the money supply more rapidly than the speed at which the amount of wealth is increasing. This is the canonical way in which inflation is framed – it will make each unit of money able to buy less wealth. Burning money will clearly have the opposite effect: decreasing the money supply and therefore making each unit of money able to buy more wealth – deflation. If however, rather than changing the supply of money, we adjust the other side of this equation, we get some interesting results.

In particular situations such as a tech boom, wealth is able to increase very rapidly. This can outpace the central bank’s planned increases to the money supply, which causes deflation. Products become cheaper (or money becomes worth more, depending on your perspective), but unlike the standard view of deflation as a sign that an economy is struggling, this is a direct result of economic success.

Equally, if we are in a situation in which wealth is decreasing, this is inherently inflationary – there is less wealth to buy with the same amount of money, so the wealth costs more (or the money is worth less). The go-to example of this happening is the oil crisis in the 1970s – suddenly oil was much less available than before, despite its usefulness to the economy being unchanged. This limitation was a dramatic reduction in the amount of wealth present in the economy, and it impacted many sectors simultaneously, from transport to manufacturing, further reducing wealth by reducing productive capacity. There was much less available to be bought, but there was the same amount of money to buy it with, so the money became worth less.

Further to this, the demand for each can be changed too. As mentioned previously, changing interest rates does this from a monetary perspective. Adjusting the appeal of holding cash versus owning assets or equities changes the demand for cash. Interest rate reductions decrease demand for cash which is inflationary, while interest rate increases have the opposite effect.

Changing the demand for wealth is a little more subtle – it requires some sort of cultural factor. As an extreme example, during the dot-com boom, the amazing stock market returns were heavily publicised, making many people that wouldn’t have ordinarily been investors want to get a piece of the action. This was a cultural shift that increased the demand for wealth. More generically, a bull market is a less extreme example of a sustained increase in demand for wealth.

A bear market is the opposite of a bull market, in which low demand results in falling prices. If anti-consumption caught on as a trend, without a corresponding increase in investment, this would similarly reduce the demand for wealth, driving prices lower. These can be collated together into a table as follows:

| Of Money | Of Wealth | |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Supply | Inflation e.g. Printing money | Deflation (More efficiency) e.g. Tech revolution |

| Decreased Demand | Inflation e.g. Lower interest rates | Deflation (Bear market) e.g. Anti-consumption |

| Decreased Supply | Deflation e.g. Burning money | Inflation (Stagflation) e.g. Supply chain disruption |

| Increased Demand | Deflation e.g. Raise interest rates | Inflation (Bull market) e.g. Stock market bubble |

The important thing here is that whilst inflation and deflation themselves obviously have a very real impact on the economy, the last column comes with other effects. In fact, the inflation/deflation is really a side effect of what is occurring to change the amount of wealth present.

IV. Consumption is Not a Good Thing

Consumption is often described in a positive way as something that “drives growth” in our economy. What actually is consumption though, looked at from this perspective?

Consumption is simply the destruction of wealth. This sounds obviously bad, but in reality some of it is unavoidable. Eating food is consumption – you are taking food (something that has value) and turning it into waste (something that has negligible value). People have to eat to survive though. You could say that without being eaten, food would spoil anyway, so it isn’t really “destruction of wealth” – the wealth was transient. That however makes the assumption that the food was going to be produced regardless. Food is only grown because it is expected to be in demand. Once something with a limited shelf life is produced, it will inevitably be consumed (either by someone, or by being wasted), and so would be best consumed in a way that helps someone survive, or generates some happiness for someone rather than being wasted. If nobody wanted the item however, the time and resources used to make it could have been spent elsewhere.

Consuming for survival is therefore difficult to argue against, but in the modern world, survival comes at a relatively small cost. (The fact that some people are unable to afford even this small cost is a failing of our society, but is something I have written about before, so will not dwell on here). The consumption that would be sufficient for everyone to survive would be a tiny fraction of our current consumption.

Using a factory to produce goods is also consumption in its own way – the factory will need more maintenance if it is in use. It gets maintained, because it is producing more wealth that it is consuming. This consumption is therefore also difficult to argue against – whilst wealth is consumed, more wealth is produced, so this is a net positive contribution.

Aside from consuming to survive and consuming to produce more, there is also consuming for enjoyment, or to increase your happiness. At this point it is important for me to note that I am not against enjoyment – life is there to be enjoyed, so I am not making any sort of absolutist argument that “doing anything other than producing or consuming to survive is bad”. We should absolutely enjoy our lives, and some amount of consumption is a reasonable price to pay for this, but we mustn’t lose sight of the reality: that consumption (by which I mean destruction of wealth) makes us poorer as a society.

Going for a walk in a forest and eating a spoonful of caviar are both activities that people engage in to gain enjoyment. Going for a walk consumes very little – you may have to eat slightly more, and it will slightly reduce the longevity of your shoes, but the wealth destruction here can be measured in pence. On the other hand, eating caviar is extremely expensive – you are taking something you have paid hundreds of pounds/dollars for and effectively flushing it down the toilet. Obviously people gain some enjoyment from the process, but the cost of that enjoyment is enormously higher.

Again – initially people not eating caviar would result in a large waste in caviar, or caviar prices reducing dramatically. This waste or drop in prices would however make caviar production less profitable, encouraging the people working in the industry, and the assets deployed in the caviar’s production to be put to other use. The expense of the caviar is indicative of the time, effort and resources deployed in creating it, which therefore indicates the amount of wealth that could otherwise have been produced had this time, effort and resource been utilised differently.

Effectively, consumption is just one big broken window fallacy – for everything that is consumed, something needs to be produced to replace it, and that effort could have been otherwise utilised had the consumption not occurred. Whilst our economy is heavily reliant upon consumption, making Keynesian policies such as stimulus undeniably necessary and effective to avoid turmoil when there is a drop in consumption, this does not change the underlying reality that any consumption ultimately reduces the amount of wealth.

This is very much reminiscent of the idea that work is an objective in itself. The philosophy that job creation is the aim of a healthy economy is completely backwards. Productivity is the thing that is desirable, whilst work is just a necessary evil to achieve productivity.

Work sucks, that’s why it isn’t called “fun”.

Bruce Bethke

Productivity cannot be achieved without work, but work is not the aim – if the same productivity could be achieved without work, that would be preferable. In fact, the poet Wendell Berry expressed it very well:

People talk about “job creation,” as if that had ever been the aim of the industrial economy. The aim was to replace people with machines.

Wendell Berry

The thing is though – I get the feeling he thinks this is a bad thing! Accomplishing more whilst working less is great, and industry has enabled this to happen. It is in exactly this way that we should view consumption – it is not the objective. Happiness (and at the very least, survival) is the thing that is desirable, whilst consumption is just a necessary evil to achieve happiness. If we can achieve the same happiness with less consumption, that is a good thing.

These two ideas are inextricably linked, because productivity is what provides us with the consumables we need to survive and to improve our happiness. The more we consume, the more work we have to do, in order to replenish the consumed items. Just as more efficient production results in less need for work, if we can attain happiness with less consumption, that will result in less need for work too. The less we work, the more time we have to spend cultivating our own happiness, so achieving the same level of happiness with less consumption should actually improve levels of happiness in our society even further.

V. Investment vs. Consumption

The alternative to consumption is investment – if you work hard, and save your money, you have contributed wealth to the world, and have not consumed it. In principle, the money you have saved is representative of the difference between the wealth you have “released into the wider economy” and the wealth you have acquired for your own personal use.

If you spend money to acquire wealth, you don’t necessarily have to consume it. You can instead accumulate assets that will persist until they degrade or are destroyed (both of which are consumption). If you use these assets to produce more, you will be contributing further wealth to the world, and will therefore generate more money. If instead, you consume them, they will be gone, and all of the effort that was put into making them will be gone too.

Fundamentally, any wealth you have acquired for your own personal use can either be consumed or maintained, and maintaining wealth is investment. This is the essence of capitalism – using capital (the wealth you control) to generate further wealth. Further distilled, you could view capitalism as the idea that investment is good, and should be rewarded. Holding money in a bank account isn’t quite the same as investment, but it is at least the absence of consumption. As we have established – some consumption is unavoidable, but if we accept the view that investment is good, then consumption cannot be desirable. After all, if investment is the creation and preservation of wealth, then consumption, as the destruction of wealth, is its opposite.

As a more abstract but ultimately easier to manage model for investment, we can consider investment in companies. Initially, let’s just consider companies issuing shares, as other transactions have more complicated mechanics. By buying shares issued by a company, you are providing them with the means to acquire further assets/employees to improve their productive capacity, and in exchange, you get to own part of this productive capacity. This is very similar to just accumulating assets yourself, but it is an abstraction layer – you don’t need to know which piece of machinery is yours, you just jointly own all of the company’s assets with all of the other shareholders.

This helps us to understand the wealth of billionaires. Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos don’t have literal billions of dollars in their bank accounts. They own a lot of shares in some very large and successful companies – this is indeed wealth rather than money. It is the easy valuation of listed companies that allows us to confuse the two, and interpret as “money” the billions of dollars worth of assets that they control.

The idea that they could “feed the world” with this wealth is a bit disingenuous. They could of course just sell the shares they own, and use it to buy food, but what is the end result of this course of action? Buying such a large amount of food, and the transport to get it to where it needs to be would be quite disruptive, and would likely drive up the costs of both food and transport, meaning that a naive calculation of “what it would cost to end world hunger” using current market prices is likely to be quite an underestimate.

Let’s ignore this glaring issue though, and plough on regardless – what does it mean, to sell a large quantity of assets in order to spend billions of dollars buying food? Whilst it is highly improbable that this financial transaction will result in the entirety of Amazon’s assets being liquidated and somehow converted into food, that is equivalent to what is occurring in wealth terms. You are going to acquire billions of dollars worth of assets, and then consume them.

Please note – I am not saying here that we shouldn’t try to feed the world, or that it would be a waste to try to save peoples lives. I am simply trying to frame the conversation in a more accurate way. It is highly misguided to make statements like “Jeff Bezos is just a greedy person, sitting on all that money when he could be saving lives”. Instead, we have to acknowledge that for us to achieve this humanitarian miracle, we would have to take wealth equivalent to a company the size of Amazon, with all of its productive capacity and therefore its ability to make life easier for millions of people, and we would have to consume it. The fact that it wouldn’t be Amazon itself that ceased to exist is irrelevant – an equivalent amount of wealth would have been consumed.

Jeff Bezos is just the custodian of this wealth. It can and should be argued whether one person should be the custodian of such a comparatively large amount of wealth. Indeed, the control that multibillionaires have over the economy, labour practices and even the government is something that should concern everybody. This is however a very different way of framing the problems with over-concentration of wealth than the self-righteous polemics against the greed of the wealthy that seem to be published regularly.

Breaking up large companies to curb monopolistic tendencies, and having strong labour and anti-lobbying regulations are very different proposals from “take wealthy people’s money and spend it”. The government does invest a lot of money in infrastructure and education, but it does consume a lot too. Few governments have the self-control to curtail their consumption sufficiently that they are able to sustain a sovereign wealth fund.

VI. Loss of Control

The amount of money that changes hands can be greater than the amount of wealth that you consume – if you hire a fancy limousine, or buy a luxury watch from a company, you can reasonably expect a significant portion of what you spend to go straight to its profit margin. Of course, the goods/services being more expensive might partially be due to a greater amount of wealth being used to provide them – the watch might be better made and longer lasting, which would take more effort, and the limousine might use more fuel than a normal car and be more expensive to maintain. Despite this though, high end brands are usually able to command a premium above and beyond that which their wares would fetch in the absence of the brand.

Any money that contributes to a company’s profit margin isn’t representative of wealth being directly consumed. After all, the profit margin is exactly the difference between the effort and expense required to make/do something and the amount you actually paid for it. Instead, this portion of the money is a transfer of the right to control that amount of wealth.

The recipients of this money can then spend it as they see fit; using it to acquire wealth, which could be invested or consumed. A company might choose to invest it in order to expand or consume it by throwing a party for their employees. A third option would be to pay a bonus to their CEO or pay a dividend to their shareholders – this would again pass on the right to control the wealth. The shareholders might choose to invest their windfall, or they might choose to consume it instead.

Once you no longer possess the money however, you do not control it, therefore you cannot determine what it is used for – whether the wealth it is used to acquire gets consumed or not. In the same way, once you have sold assets, you don’t control them anymore, and you can’t stop someone from consuming them. Just because you have cash in the bank, doesn’t mean that the wealth that cash represents can’t be destroyed. The wealth you sold is not directly tied to the cash, so the cash won’t become worthless if the wealth is consumed; instead as mentioned, this loss of wealth is distributed across all cash as inflation.

How do you stop wealth you control from being consumed, without having to manage a load of assets yourself? Well, thankfully in the modern day this is really very easy – you buy shares. Rather than having to maintain a bunch of assets, and having to work out how to use them most productively, owning shares in companies means that you are effectively employing the company’s executives to do this for you. Companies are set up to maximise shareholder profit, which means that their goal is to use the wealth they control to generate as much additional wealth as they can.

As with most things, this can break down if taken to the extreme. Companies can generate negative externalities that their profitability does not capture, such as environmental damage, employee exploitation or monpolistic tendencies. From a personal finance perspective, you should also have a well diversified portfolio, so that you are not over-exposed to any particular asset class or location. In general though, this “maximise shareholder profit” maxim is exactly what you want, if you intend to use your wealth to generate more wealth, rather than risk it being consumed.

VII. Capitalism isn’t Consumerism

In my last post, I talked about capitalism, and how it is often conflated with a number of societal ills, including consumerism. As above – the accumulation of wealth in order to use it to create further wealth is the core tenet of capitalism, making consumerism fundamentally anti-capitalist. How then do we end up with consumerism in a capitalist society?

This is an important question, as it is demonstrably the case that our society is quite consumerist, despite ostensibly being based on capitalist principles. We can look no further than Adam Smith himself – the “father of capitalism” for an insight into why this is:

Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production; and the interest of the producer ought to be attended to, only so far as it may be necessary for promoting that of the consumer.

Adam Smith – The Wealth Of Nations

As this article argues, Adam Smith didn’t foresee the full extent of the industrial revolution, however in a certain context, he is not wrong. Ultimately, most of what we do is aimed at increasing our happiness in some way. It is just a question of whether we are consuming (in order to satisfy ourselves right now), or investing (in order to be able to satisfy ourselves more or more cheaply in the future).

Investment in productive capacity can enable us to produce things more efficiently, allowing us to satisfy ourselves the same amount, but consuming less wealth while doing so. Investment in the arts can give us more art to enjoy, allowing us to satisfy ourselves more. It would be unhelpful to suggest that we not consume anything beyond what is necessary to survive and increase our production, as this flies in the face of everyone’s ultimate goal of living a happy contented life. That said, if we understand the trade-off between consuming now versus investing for the future, it can help us to improve our happiness and our society in the long term.

I will argue that there are two forces pushing a capitalist system towards consumerism, and that these forces do make consumerism a natural consequence of capitalism when taken to its extreme. However, rather than rejecting capitalism entirely as a way to stem the tide of consumerism, this tells us instead where we need to regulate and rein in capitalism.

VIII. Status Symbols

The first force is the social pressure on people to appear “high status”. Different societies and cultures have different measures of status – in Tang Dynasty China, being accepted into the civil service was a sign of success in life, and such positions were highly sought after, whilst in the Roman Republic, victorious military leaders were the most lauded citizens. In the middle of the 20th century, professorship was one of the most respectable careers, with academic success being prized even if it wasn’t particularly lucrative.

In our modern society, there are a couple of key sources of status – fame and wealth. The former often begets the latter (c.f. Film stars being able to command large fees), whilst the latter is increasingly resulting in a kind of fame (with Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg becoming household names).

Status games are inevitable – some people may be immune to the desire for high status, but most are not. Capitalism makes a value judgement that wealthy people have done something good – produced more and consumed less, which means that individuals with high wealth are natural role models within a capitalist society. This is not in itself necessarily a problem, but the problem arises when people care more about appearance than substance. Wealthy people are able to consume a lot more than others, so if they care about whether or not they appear wealthy, they might choose to consume more than they otherwise would.

The aforementioned caviar is of course a good example of this. At £20,000 per kilogram, Beluga caviar isn’t a thousand times more delicious than steak – it allows people to demonstrate their social status through conspicuous consumption. Luxury yachts are not quite consumption in themselves – they are an asset that could be put to productive use, but they are usually not. This makes their purpose fundamentally one of conspicuous consumption – they take money to maintain, and even more money to staff and to use. All of this consumes wealth, and it isn’t done to enable the yacht to create more wealth.

Conspicuous consumerism doesn’t just apply to the wealthy people that can do so without difficulty – in an attempt to appear “high status” many people that could live a perfectly comfortable life end up in debt as they try to “keep up with the Joneses”, consuming more than they need in order to signal a greater wealth than they actually have.

This is not to say that all of these “high status” actions are terrible. For example, getting a taxi isn’t always an unnecessary expense. If you drove yourself, you would have been consuming your own time and effort. This means that if your time is particularly valuable and productive, perhaps using a driver would be a net positive, which is why most CEOs have chauffeurs.

All this being said, conspicuous consumption is not a problem that is unique to capitalism – it has been observed in one guise or another for as long as we have recorded history. For this reason, it is not easily resolved, and capitalism shouldn’t take all of the blame, but valuing the accumulation of wealth may well exacerbate the issue. Some cultures have developed a stigma attached to conspicuous consumerism, viewing it as “tacky”, which may serve as a useful opposing force, though cultivating this aspect of a culture is likely to be quite a difficult endeavour.

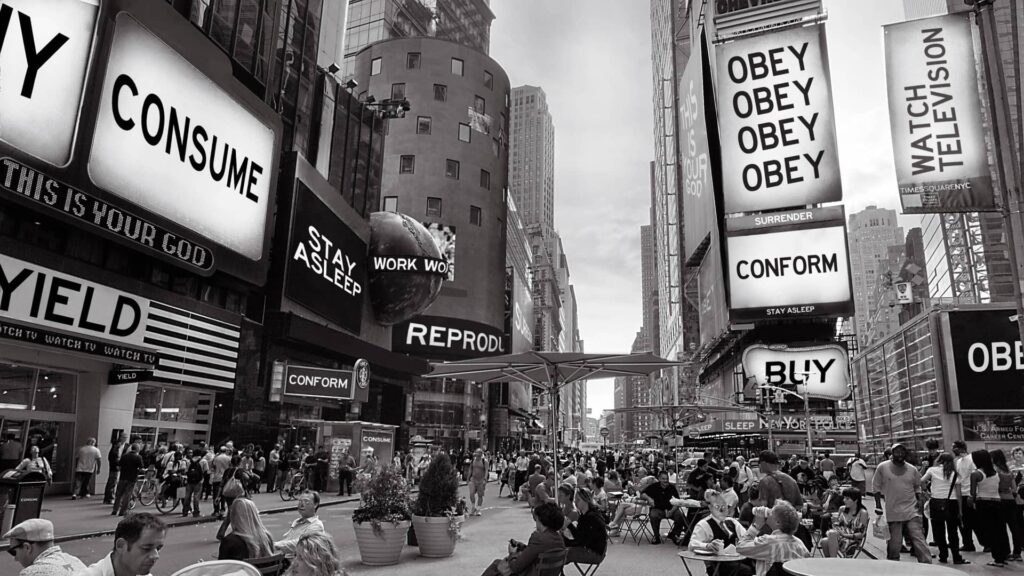

IX. Advertising

The other key force that leads capitalism down the path towards consumerism is advertising. Advertisements can simply inform people that a product exists – arguably a useful service. This is however not usually the limit of the advertiser’s power, as over time we have become more sophisticated at manipulating people, and even our culture itself through the medium of advertising (c.f. Women’s shaving products). Companies are now adept at inventing insecurities for people to worry about and spend money on – they can tell people what they want, and therefore artificially increase demand for consumption.

Much of this advertising plays on encouraging the kind of status games discussed in the previous section, but even aside from that, there is a lot of money to be made in convincing people to be unsatisfied by things that previously made them happy. A company can’t make much money from you if you are content with what you have, so it is in their interest to make you feel like you are missing out.

Rather than living happy contented lives, taking leisurely strolls in nature, comfortable in the knowledge that food is readily available and cheap, we instead persist in the rat-race of 9-to-5 jobs earning money so that we can consume more. The latest iPhone, a new widescreen TV, caviar, you name it – all reduced to rubbish and discarded when the next one comes out, having given us fleeting enjoyment and leaving us with no more wealth than we started with. The people producing these consumables have found an exploit in the system – they are capitalists, but they have used advertising to convince other people to be non-capitalist.

There are many people living paycheck to paycheck – 41% of the UK don’t have enough in savings to live for a month without income. To be very clear – there are many of these people that have no choice – they have very low incomes, and so are just consuming to survive. After the state pension, the largest DWP program is Housing Benefit with 3.8 million claimants. All of these people, whether pensioners, unemployed or working poor must have very little income, so it is no surprise that they are unable to make savings (also, given the way benefits are administered, if they saved too much, they would become ineligible for benefits). In its mission to reduce poverty, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation also collects data on the working poor, and they calculate that there were around 4 million people that counted as working poor in 2019. There will be significant overlap between people on Housing Benefit and the JRF’s working poor figure, but if we make the (for these purposes) very conservative assumption that there isn’t any overlap, that would mean there were 7.8 million people in the UK that are completely unable to make savings.

This is still less than 15% of the adult population of the UK though, so what about the other 26% of people that are not living in poverty, but still live paycheck to paycheck? These people are earning money, and spending it immediately on items they consume. Unlike the poorest citizens, who are consuming in order to survive, and need government assistance to be able to manage that, these people are consuming because they want to. They remain unable to afford to invest – paying their money to the capitalists, rather than being capitalists themselves. They are the archetypal consumers.

X. The Incentive to Encourage Consumption

After all, if you buy something from a company, they get to keep whatever profit margin they are making – they have no further obligation to you. If you invested that money into the company instead, it would have to pay you a share of the dividends – effectively diluting the current owners.

Wait, I hear you say – this only happens when companies are issuing new shares! Buying shares on the stock market doesn’t usually dilute anyone or create new obligations, it just increases their share price.

Well – assuming that a company isn’t issuing shares, and that you’re just buying them on the open market, it is true that investing in a company doesn’t dilute anyone’s shareholding (unless they happen to choose to sell shares at the same time). What it does do however, is slightly increase the demand for shares. This can be looked at in a couple of ways:

- The person you bought the shares off now has money they have to do something with, and assuming they want to invest it, they need to find something to invest it in. They invest it in another company, setting off a cascade of buyers and sellers until at some point in the chain, someone invests in a share issue, a bond or some other form of investment that directly adds money to the system, allowing a company to acquire some equipment/employees.

- Alternatively, you can look at it another way – although share prices in a liquid market are very elastic, it is still the case that buying shares will shift the share price a small amount. If demand goes up enough, it will increase the price of shares, which will decrease their yield. This lower yield makes other riskier shares more attractive, again causing a cascade effect in which an investment in a blue-chip company can marginally increase the demand for new shares in a start-up.

Both of these perspectives give you a result that is less desirable for the company’s owners than just making a small profit out of your consumption. This brings us back to advertising – if you can encourage people to consume rather than invest, you get more money with no strings attached. Promoting consumerist attitudes is profitable for a great many companies, so they advertise aggressively to make people want more stuff.

XI. Conclusion

So – consumption is not desirable. Whilst consumption is unavoidable, and it is in a limited sense the end goal of production, the excessive or conspicuous consumption that is consumerism is in fact anti-capitalist. Despite this, I have argued that consumerism occurs when capitalism is allowed to progress unregulated. When companies are allowed too much scope to influence people and culture through advertising, consumerism becomes inevitable.

To combat this, strong advertising regulations are critical – the UK’s advertising standards agency generally does a good job of this, ensuring that adverts are factual and not misleading. Adverts in the US don’t appear to have any such limitations, which leads to claims like “Pop-tarts – a good source of vitamins” – these statements rather amusingly have to be covered up before such products can be sold in the UK.

Personally though, I don’t think the UK goes far enough – adverts are still able to make people unhappy with their current situation, pushing “aspirational” lifestyles that stoke people’s envy. We have done something like this with alcohol advertising, for which there are very stringent rules about not making drinking look “cool” to young people and not encouraging excessive drinking.

Of course, to have strong regulations around advertising, companies need to be prevented from becoming too large and powerful. Once a company is large enough, it either becomes too important to a country’s economy for politicians to be able to risk disagreeing with its board (c.f. Samsung’s influence in South Korea), or it simply becomes able to buy (oh, sorry – I meant “lobby”) politicians.

This means that in a healthy capitalist society, companies need to be prevented from becoming too large or powerful, otherwise they may start engaging in these harmful behaviours. Again, the UK has this to some extent in the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), whose main brief is to police monopolistic behaviours that might harm the interests of “consumers”. This specific focus on consumers does however seem to often miss the impacts of mergers on the wider economy (suppliers, competitors, supporting industries, etc.), which are important to consider when trying to avoid excessive concentration of power. The CMA’s decision to block a merger between Sainsbury’s and Asda in 2019 was unexpected given previous precedent, but I am inclined to see this change in approach as long overdue – together they would have made up over 30% of the UK’s grocery market.

Concerns about concentration of power are also relevant for individuals, so it is important to consider ways in which we can limit the power of wealthy people in a capitalist society. Further to this, as mentioned at the start of this post, anything that might subvert the link between the amount of wealth someone produces and the money they receive for it needs to be carefully monitored and minimised. Worker exploitation and poorly negotiated contracts are obvious things that are often regulated by governments, but taxes also need to be carefully managed to not disrupt growth by introducing perverse incentives.

Controls and regulations that would be beneficial to a capitalist society:

- Limits to advertising – ensuring adverts are factual, not misleading and are not trying to make people unhappy with their current situation.

- More restrictions around mergers between large companies, and a greater willingness to break up large companies that hold too much market share.

- Strong restrictions around lobbying, bribery and the “revolving door between government and business”. Better pay for politicians and government officials (as is done in Singapore) might help this.

- Reducing the barriers to small investors, to encourage all people to partake in the ownership of companies.

- Strong penalties for business practices that involve large businesses bankrupting small companies in order to buy them or their intellectual property at bargain prices.

Does this mean we should give tax cuts to the rich, rather than paying welfare to the poor? No! Survival is important – it shouldn’t need to be said that people dying is bad. Developed countries are now at the point where survival driven consumption is tiny in proportion to the sizes of their economies. With the increasing likelihood of AI being developed in the next few years, we need to be sure that the bounties of a successful economy are of benefit to all people. Arguments that suggest that allowing people to die might be economically beneficial have lost sight of what the goal of humanity should be. We want an economy that makes life good and happy for people – if the economy would be more efficient if humans were wiped out, so that production could be higher and consumption lower, that is missing the point completely.

Does this mean that we should stop worrying about wealth inequality? No! Control of wealth is important, and if too few people control too much wealth there are all sorts of problems that arise. Concentrated wealth is like putting all of your eggs in one basket – what if someone who has consistently made good investment decisions suddenly stops being competent? If any individual is in a position where a mis-step by them could crash the economy, that is a huge risk. Concentrated wealth is also a risk to democracy, as anyone with an amount of wealth comparable to a small country has the power to apply significant leverage to politicians (even in a big country) to get what they want. Too few people making investment decisions in an economy reduces the diversity of ideas – the beauty and efficiency of markets is due to the effect that a large enough number of people’s estimates for the value of an item converges on the item’s actual value. By reducing the number of people actually participating in the market, you lose a huge amount of information.

Hopefully this explains why I think that capitalism has the potential to be a good thing in its own right. Also, it might explain why I find the suggestion by the UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, that people help the UK’s economy by spending all the money they have saved up over the last 9 months, quite so infuriating.

One Reply to “Capitalism as a Social Cause”